RESEARCH AND ORIENTATION WORKSHOP ON FORCED MIGRATION

Winter Course on Forced Migration, 2005

Course Readings

MODULE A

Forced Migration,racism,immigration, and xenophobia

Etienne Balibar, “Is There a ‘Neo- Racism’?” in Etienne Balibar and Immanuel Wallerstein, Race, Nation, Class – Ambiguous Identities (Verso, 1991)

B.S. Chimni, International Refugee Law – A Reader (Sage Publications, 2003), section 5

Samir Kumar Das, “Wars, Population Movements and State-Formation-Private in South Asia” in Ranabir Samaddar (ed.), Peace Studies I (Sage Publications, 2004)

Paula Banerjee, “Borders as Unsettled Markers – The Sino-Indian Border” in Ranabir Samaddar (ed.), Peace Studies I (Sage Publications, 2004)

Asha Hans, “Women Across Borders in Kashmir – The Continuum of Violence” in Ranabir Samaddar (ed.), Peace Studies I (Sage Publications, 2004)

Monirul Hussain, “Nationalities, Ethnic Processes and Violence in India’s North-east” in Ranabir Samaddar (ed.), Peace Studies I (Sage Publications, 2004)

Ranabir Samaddar (ed.), Refugees and the State (Sage Publications, 2003), chapters 1-3, 6, 9.

Ranabir Samaddar, The Marginal Nation (Sage Publications, 1999), chapters 1-4, 13

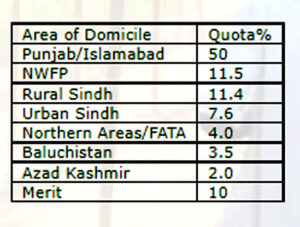

REFUGEE WATCH, “Scrutinising the Land Settlement Scheme in Bhutan”, No. 9, March 2000

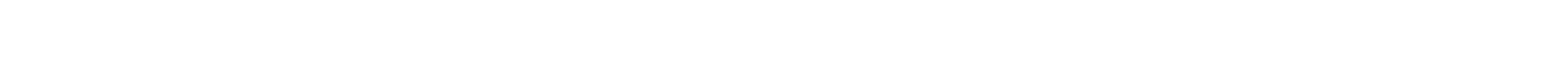

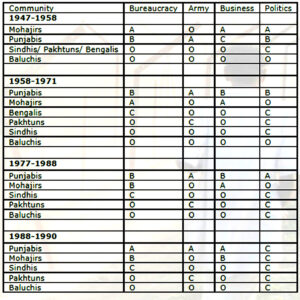

REFUGEE WATCH, “Mohajirs: The Refugees by Choice”, No. 14, June 2001

REFUGEE WATCH, “Displacing the People the Nation Marches Ahead in Sri Lanka”, No. 15, September 2001

MODULE B

Gender dimensions of forced migration, vulnerabilities, and justice

Paula Banerjee, Sabyasachi Basu Ray Chaudhury and Samir Das, Internal Displacement in South Asia, chapter 9.

B.S. Chimni, International Refugee Law – A Reader (Sage Publications, 2003), section 1

Ritu Menon and Kamla Bhasin, Borders and Boundaries, chapter 3.

Paula Banerjee,”Refugee Women and the Fundamental Inadequacies in Institutional Responses in South Asia”, in Joshva Raja, Refugees and their Right to Communicate

Ranabir Samaddar (ed.), Refugees and the State (Sage Publications, 2003), chapter 9.

Ranabir Samaddar, The Marginal Nation (Sage Publications, 1999), chapter 12.

Refugee Watch, Nos. 10-11

CEDAW : http://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/econvention.htm

UNHCR Policy on Refugee Women

http://www.safhr.org/refugee_watch10&11_92.htm

REFUGEE WATCH: “Select UNICEF Policy Recommendation on the Gender Dimensions of Internal, No. Displacement”,10 & 11, July 2000

http://www.safhr.org/refugee_watch10&11_92.htm

REFUGEE WATCH: “Dislocated Subjects : The Story of Refugee Women”, No. 10 & 11, July 2000

REFUGEE WATCH: “War and Its Impact on Women in Sri Lanka”, No. 10 & 11, July 2000

REFUGEE WATCH: Afghan Women In Iran

REFUGEE WATCH: “Refugee Women of Bhutan”, No. 10 & 11, July 2000

REFUGEE WATCH: “Rohingya Women – Stateless and Oppressed in Burma”, No. 10 & 11, July 2000

REFUGEE WATCH: “Dislocating Women and Making the Nation”, No. 17, December 2002

MODULE C

International, Regional, and the National Legal Regimes of Protection, Sovereignty and the Principle of Resposibility

Paula Banerjee, Sabyasachi Basu Ray Chaudhury and Samir Das, Internal Displacement in South Asia, Epilogue

B.S. Chimni, International Refugee Law – A Reader (Sage Publications, 2003)

Who is a Refugee?, Pgs. 1-81; Asylum, Pgs. 82-160; Rights and Duties of a Refugee, Pgs. 161-209

Ranabir Samaddar (ed.), Refugees and the State (Sage Publications, 2003), chapters 10-11.

Refugee Watch No.4 (December 1998) articles by Sarbani Sen and Brian Gorlick.

F-e-material 1 – International Humanitarian Law and Human Rights Law

Document printed from the website of the ICRC.

URL: http://www.icrc.org/web/eng/siteeng0.nsf/html/57JMRT

International Committee of the Red Cross

F-e-material 2 –“A Patchwork Protection Regime; Internal Displacement in International Law and Institutional Practice” / David Fisher

Convention Against Torture

CAT: http://www.un.org/documents/ga/res/39/a39r046.htm

REFUGEE WATCH

MODULE D

Internal Displacement with Special Reference to Causes, Linkages, and Responses

Paula Banerjee, Sabyasachi Basu Ray Chaudhury and Samir Das, Internal Displacement in South Asia.

Addressing Internal Displacement: A Framework For National Responsibility

Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement

E-material: Protection of Internally Displaced Persons: Inter-Agency Standing Committee Policy Paper

E-e-material2: Sovereignty as Responsibility: The Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement/ Roberta Cohen

E-e-material3:An Overview of Revisions to the World Bank Resettlement Policy

MODULE E

Resource politics, environmental degradation,violence and internal displacement and forced migration

“Ethnic Politics and Land Use : Genesis of Conflicts in India’s North-East” / Sanjay Barbora in Economic & Political Weekly, March 30, 2002

“Globalization, Class and Gender Relations : The Shrimp Industry In South-western Bangladesh” / Meghna Guhathakurta, unpublished

Report of Workshop on Engendering Resettlement & Rehabilitation Policies and Programmes in India, Mohammed Asif, Lyla Mehta and Harsh Mander, November 2002

“Development Induced Displacement in Pakistan” / Atta ur Rehman Sheikh, in Refugee Watch, No. 15

“Scrutinizing the Land Resettlement Scheme in Bhutan”, Jagat Acharya, in Refugee Watch, No. 9

MODULE F

Ethics of care and justice

“Trust and the refugee experience” / Pradip Kumar Bose, in Refugee Watch, No. 5 & 6

“Development, displacement and international ethics” (mimeo.) / Peter Penz

“In life, in death: Power and rights” (mimeo.) / Ranabir Samaddar

“Power, Fear, Ethics” / Ranabir Samaddar, in Refugee Watch, No. 14

To what extent is it correct so speak of a neo-racism? The question is forced upon us by current events in forms which differ to some degree from one country to another, but which suggest the existence of a transnational phenomenon. The question may, however, be understood in two senses. On the one hand, -are we seeing a new historical upsurge of racist movements and policies which might be explained by a crisis conjuncture or by other causes? On the other hand, in its themes and its social significance, is what we are seeing only a new racism, irreducible to earlier ‘models’, or is it a mere tactical adaptation? I shall concern myself here primarily with this second aspect of the question.[i]

First of all, we have to make the following observation. The neoracism hypothesis, at least so far as France is concerned, has been formulated essentially on the basis of an internal critique of theories, of discourses tending to legitimate policies of exclusion in terms of anthropology or the philosophy of history. Little has been done on finding the connection between the newness of the doctrines and the novelty of the political situations and social transformations, which have given them a purchase. I shall argue in a moment that the theoretical dimension of racism today, as in the past, is historically essential, but that it is neither autonomous nor primary. Racism – a true ‘total social phenomenon’ inscribes itself in practices (forms of violence, contempt, intolerance, humiliation and exploitation), in discourses and representations, which are so many intellectual elaborations of the phantasm of prophylaxis or segregation (the need to purify the social body, to preserve ‘one’s own’ or ‘our’ identity from all forms of mixing, interbreeding or invasion) and which are articulated around stigmata of otherness (name, skin colour, religious practices). It therefore organizes affects (the psychological study of these. has concentrated upon describing their obsessive character and also their ‘irrational’ ambivalence) by conferring upon them a stereotyped form, as regards both their ‘objects’ and their ‘subjects’. It is this combination of practices, discourses and representations in a network of affective stereotypes which enables us to give an account of the formation of a racist community (or a community of racists, among whom there exist bonds of ‘imitation’ over a distance) and also of the way in which, as a mirror image, individuals and collectivities that are prey to racism (its ‘objects’) find themselves constrained to see themselves as a community.

But however absolute that constraint may be, it obviously can never be cancelled out as constraint for its victims: it can neither be interiorized without conflict (see the works of Memmi) nor can it remove the contradiction which sees an identity as community ascribed to collectivities which are simultaneously denied the right to define themselves (see the writings of Frantz Fanon), nor, most importantly, can it reduce the permanent excess of actual violence and acts over discourses, theories and rationalizations. From the point of view of its victims, there is, then, an essential dissymmetry within the racist complex, which confers upon its acts and ‘actings out’ undeniable primacy over its doctrines, naturally including within the category of actions not only physical violence and discrimination, but words themselves, the violence of words in so far as they are acts of contempt and aggression. Which leads us, in a first phase, to regard shifts in doctrine and language as relatively incidental matters: should we attach so much importance to justifications which continue to retain the same structure (that of a denial of rights) while moving from the language of religion into that of science, or from the language of biology into the discourses of culture or history, when in practice these justifications simply lead to the same old acts?

This is a fair point, even a vitally important one, but it does not solve all the problems. For the destruction of the racist complex presupposes not only the revolt of its victims, but the transformation of the racists themselves and, consequently, the internal decomposition of the community created by racism. In this respect, the situation is entirely analogous, as has often been said over the last twenty years or so, with that of sexism, the overcoming of which presupposes both the revolt of women and the break-up of the community of ‘males’. Now, racist theories are indispensable in the formation of the racist community. There is in fact no racism without theory (or theories). It would be quite futile to inquire whether racist theories have emanated chiefly from the elites or the masses, from the dominant or the dominated classes. It is, however, quite clear that they are ‘rationalized’ by intellectuals. And it is of the utmost importance that we enquire into the function fulfilled by the theory building of academic racism (the prototype of which is the evolutionist anthropology of ‘biological’ races developed at the end of the nineteenth century) in the crystallization of the community which forms around the signifier, ‘race’.

This function does not, it seems to me, reside solely in the general organizing capacity of intellectual rationalizations (what Gramsci called their ‘organicity’ and Auguste Comte their ‘spiritual power’) nor in the fact that the theories of academic racism elaborate an image of community, of original identity in which individuals of all social classes may recognize themselves. It resides, rather, in the fact that the theories of academic racism mimic scientific discursivity by basing themselves upon visible ‘evidence’ (whence the essential importance of the stigmata of race and in particular of bodily stigmata), or, more exactly, they mimic the way in which scientific discursivity articulates ‘visible facts’ to ‘hidden causes’ and thus connect up with a spontaneous process of theorization inherent in the racism of the masses.[ii] I shall therefore venture the idea that the racist complex inextricably combines a crucial function of misrecognition (without which the violence would not be tolerable to the very people engaging in it) and a ‘will to know’, a violent desire for immediate knowledge of social relations. These are functions, which are mutually sustaining since, both for individuals and for social groups, their own collective violence is a distressing enigma and they require an urgent explanation for it. This indeed is what makes the intellectual posture of the ideologues of racism so singular, however sophisticated their theories may seem. Unlike for example theologians, who must maintain a distance (though not an absolute break, unless they lapse into ‘gnosticism’) between esoteric speculation and a doctrine designed for popular consumption, historically effective racist ideologues have always developed ‘democratic’ doctrines which are immediately intelligible to the masses and apparently suited from the outset to their supposed low level of intelligence, even when elaborating elitist themes. In other words, they have produced doctrines capable of providing immediate interpretative keys not only to what individuals are experiencing but to what they are in the social world (in this respect, they have affinities with astrology, characterology and so on), even when these keys take the form of the revelation of a ‘secret’ of the human condition (that is, when they include a secrecy effect essential to their imaginary efficacity: this is a point which has been well illustrated by Leon Poliakov)[iii]

This is also, we must note, what makes it difficult to criticize the content and, most importantly, the influence of academic racism, In the very construction of its theories, there lies the presupposition that the ‘knowledge’ sought ‘and desired by the masses is .an elementary knowledge which simply justifies them in their spontaneous feelings or brings them back to the truth of their instincts. Bebel, as is well known, called anti-Semitism the ‘socialism of fools’ and Nietzsche regarded it more or less as the politics of the feeble-minded (though this in no way prevented him from taking over a large part of racial mythology himself). Can we ourselves, when we characterize racist doctrines as strictly demagogic theoretical elaborations, whose efficacity derives from the advance response they provide for the masses’ desire for knowledge, escape this same ambiguops position? The category of the ‘masses’ (or the ‘popular’) is not itself neutral, but communicates directly with the logic of a naturalization and racization of the social. To begin to dispel this ambiguity, it is no doubt insufficient merely to examine the way the racist ‘myth’ gains its hold upon the masses; we also have to ask why other sociological theories, developed within the framework of a division between ‘intellectual’ and ‘manual’ activities (in the broad sense), are unable to fuse so easily with this desire to know. Racist myths (the ‘Aryan myth’, the myth of heredity) are myths not only by virtue of their pseudo-scientific content, but in so far as they are forms of imaginary transcendence of the gulf separating intellectuality from the masses, forms in dissociable from that implicit fatalism which imprisons the masses in an allegedly natural infantilism.

We can now turn our attention to ‘neo-racism’. What seems to pose a problem here is not the fact of racism, as I have already pointed out practice being a fairly sure criterion (if we do not allow ourselves to be deceived by the denials of racism which we meet among large sections of the political class in particular, which only thereby betrays the complacency and blindness of that group) – but determining to what extent the relative novelty of the language is expressing a new and lasting articulation of social practices and collective representations, academic doctrines and political movements. In short, to use Gramscian language, we have to determine whether something like hegemony is developing here.

The functioning of the category of immigration as a substitute for the notion of race and a solvent of ‘class consciousness’ provides us with a first clue. Quite clearly, we are not simply dealing with a camouflaging operation, made necessary by the disrepute into which the term ‘race’ and its derivatives has fallen, nor solely with a consequence of the transformations of French society. Collectivities of immigrant workers have for many years suffered discrimination and xenophobic violence in which racist stereotyping has played an essential role. The interwar period, another crisis era, saw the unleashing of campaigns in France against ‘foreigners’, Jewish or otherwise, campaigns, which extended beyond the activities of the fascist movements and which found their logical culmination in the Vichy regime’s contribution to the Hitlerian enterprise. Why did we not at that period see the ‘sociological’ signifier definitively replace the ‘biological’ one as the key representation of hatred and fear of the other? Apart from the force of strictly French traditions of anthropological myth, this was probably due, on the one hand, to the institutional and ideological break which then existed between the perception of immigration (essentially European) and colonial experience (on the one side, France ‘was being invaded’, on the other it ‘was dominant’) and, on the other hand, because, of tilt; absence of a new model of articulation between states, peoples and cultures on a world scale.[iv] The two reasons are indeed linked. The new racism is racism of the era of ‘decolonization’, of the reversal of population movements between the old colonies and the old metropolises, and the division of humanity within a single political space. Ideologically, current racism, which in France centres upon the immigration complex, fits into a framework of ‘racism without races’, which is already widely developed in other countries, particularly the Anglo-Saxon ones. It is racism whose dominant theme is not biological heredity but the insurmountability of cultural differences, a racism, which, at first sight, does not postulate the superiority of certain groups or peoples in relation to others but ‘only’ the harmfulness of abolishing frontiers, the incompatibility of life-styles and traditions; in short, it is what: e. A. Taguieff has rightly called a differentialist racism.[v]

To emphasize the importance of the question, we must first of all bring out the political consequences of this change. The first is a destabilization of the defences of traditional anti-racism in so far as its argumentation finds itself attacked from the rear, if not indeed turned against itself (what Taguieff excellently terms the’ turn-about effect’ of differentialist racism). It is granted from the outset that races do not constitute isolable biological units and that in reality there are no ‘human races’. It may also be admitted that the behaviour of individuals and their ‘aptitudes’ cannot be explained in terms of their blood or even their genes, but are the result of their belonging to historical ‘cultures’. Now anthropological culturalism, which is entirely orientated towards the recognition of the diversity and equality of cultures – with only the polyphonic ensemble constituting human civilization – and also their transhistorical permanence, had provided the humanist and cosmopolitan anti-racism of the post-war period with most of its arguments. Its value had been confirmed by the contribution it made to the struggle against the hegemony of certain standardizing imperialisms and against the elimination of minority or dominated civilizations – ‘ethnocide’. Differentialist racism takes this argumentation at its word. One of the great figures in anthropology, Claude Levi-Strauss, who not so long ago distinguished himself by demonstrating that all civilizations are equally complex and necessary for the progression of human thought, now in ‘Race and Culture’ finds himself enrolled, whether he likes it or not, in the service of the idea that the ‘mixing of cultures’ and the suppression of ‘cultural distances’ would correspond to the intellectual death of humanity and would perhaps even endanger the control mechanisms that ensure its biological survival.[vi] And this ‘demonstration’ is immediately related to the ‘spontaneous’ tendency of human groups (in practice national groups, though the anthropological significance of the political category of nation is obviously rather dubious) to preserve their traditions, and thus their identity. What we see here is that biological or genetic naturalism is not the only means of naturalizing human behaviour and social affinities. At the cost of abandoning the hierarchical model (though the abandonment is more apparent than real, as we shall see), culture can also function like a nature, and it can in particular function as a way of locking individuals and groups a priori into a genealogy, into a determination that is immutable and intangible in origin.

But this first turn-about effect gives rise to a second, which turns matters about even more and is, for that, all the more effective: if insurmountable cultural difference is our true ‘natural milieu’, the atmosphere indispensable to us if we are to breathe the air of history, then the abolition of that difference will necessarily give rise to defensive reactions, ‘interethnic’ conflicts and a general rise in aggressiveness. Such reactions, we are told, are ‘natural’, but they are also dangerous. By an astonishing volte-face, we here see the differentialist doctrines themselves proposing to explain racism (and to ward it off).

In fact, what we see is a general displacement of the problematic. We now move from the theory of races or the struggle between the races in human history, whether based on biological or psychological principles, to a theory of ‘race relations’ within society, which naturalizes not racial belonging but racist conduct. From the logical point of view, differentialist racism is a meta-racism, or what we might call a ‘secondposition’ racism, which presents itself as having drawn the lessons from the conflict between racism and anti-racism, as a politically operational theory of the causes of social aggression. If you want to avoid racism, you have to avoid that ‘abstract’ anti-racism which fails to grasp the psychological and sociological laws of human population movements; you have to respect the ‘tolerance thresholds’, maintain ‘cultural distances’ or, in other words, in accordance with the postulate that individuals are the exclusive heirs and bearers of a single culture, segregate collectivities (the best barrier in this regard still being national frontiers). And here we leave the realm of speculation to enter directly upon political terrain and the interpretation of everyday experience, Naturally, ‘abstract’ is not an epistemological category, but a value judgment which is the more eagerly applied when the practices to which it corresponds are the more concrete or effective: programmes of urban renewal, anti-discrimination struggles, including even positive discrimination in schooling and jobs (what the American New Right calls ‘reverse discrimination’; in France too we are more and more often hearing ‘reasonable’ figures who have no connection with any extremist movements explaining that ‘it is anti-racism which creates racism’ by its agitation and its manner of ‘provoking’ the mass of the citizenry’s national sentiments).[vii]

It is not by chance that the theories of differentialist racism (which from now on will tend to present itself as the true anti-racism and therefore the true humanism) here connect easily with ‘crowd psychology’, which is enjoying something of a revival, as a general explanation of irrational movements, aggression and collective violence, and, particularly, of xenophobia. We can see here the double game mentioned above operating fully: the masses are presented with an explanation of their own ‘spontaneity’ and at the same time they are implicitly disparaged as a ‘primitive’ crowd. The neo-racist ideologues are not mystical heredity theorists, but ‘realist’ technicians of social psychology…

In presenting the turn-about effects of neo-racism in this way, I am doubtless simplifying its genesis and the complexity of its internal variations, but I want to bring out what is strategically at stake in its development. Ideally one would wish to elaborate further on certain aspects and add certain correctives, but these can only be sketched out rudimentarily in what follows.

The idea of a ‘racism without race’ is not as revolutionary as one might imagine. Without going into the fluctuations in the meaning of the word ‘race’, whose historiosophical usage in fact predates any reinscription of ‘genealogy’ into’ genetics’, we must take on board a number of major historical facts, however troublesome these may be (for a certain anti-racist vulgate, and also for the turn-abouts forced upon it by neo-racism).

A racism, which does not have the pseudo-biological concept of race as its main driving force has always existed, and it has existed at exactly this level of secondary theoretical elaborations. Its prototype is anti-Semitism. Modern anti-Semitism – the form which begins to crystallize in the Europe of the Enlightenment, if not indeed from the period in which the Spain of the Reconquista and the Inquisition gave a statist, nationalistic inflexion to theological anti-Judaism – is already a ‘culturalist’ racism. Admittedly, bodily stigmata playa great role in its phantasmatics, but they do so more as signs of a deep psychology, as signs of a spiritual inheritance rather than a biological heredity.[viii] These signs are, so to speak, the more revealing for being the less visible and the Jew is more ‘truly’ a Jew the more indiscernible he is. His essence is that of a cultural tradition, a ferment of moral disintegration. Anti-Semitism is supremely ‘differentialist’ and in many respects the whole of current differentialist racism may be considered, from the formal point of view, as a generalized anti-Semitism. This consideration is particularly important for the interpretation of contemporary Arabophobia, especially in France, since it carries with it an image of Islam as a ‘conception of the world’, which is incompatible with Europeanness and an enterprise of universal ideological domination, and therefore a systematic confusion of ‘Arabness’ and ‘Islamicism’.

This leads us to direct our attention towards a historical fact that is even more difficult to admit and yet crucial, taking into consideration the French national form of racist traditions. There is, no doubt, a specifically French branch of the doctrines of Aryanism, anthropometry and biological geneticism, but the true ‘French ideology’ is not to be found in these: it lies rather in the idea that the culture of the ‘land of the Rights of Man’ has been entrusted with a universal mission to educate the human race. There corresponds to this mission a practice of assimilating dominated populations and a consequent need to differentiate and rank individuals or groups in terms of their greater or lesser aptitude for – or resistance to – assimilation. It was this simultaneously subtle and crushing form of exclusion/inclusion, which was deployed in the process of colonization and the strictly French (or ‘democratic’) variant of the ‘White man’s burden’. I return in later chapters to the paradoxes of universalism and particularism in the functioning of racist ideologies or in the racist aspects of the functioning of ideologies.[ix]

Conversely, it is not difficult to see that, in neo-racist doctrines, the suppression of the theme of hierarchy is more apparent than real. In fact, the idea of hierarchy, which these theorists may actually go so far as loudly to denounce as absurd, is reconstituted, on the one hand, in the practical application of the doctrine (it does not therefore need to be stated explicitly), and, on the other, in the very type of criteria applied in thinking the difference between cultures (and one can again see the logical resources of the ‘second position’ of meta-racism in action).

Prophylactic action against racial mixing in fact occurs in places where the established culture is that of the state, the dominant classes and, at least officially, the ‘national’ masses, whose style of life and thinking is legitimated by the system of institutions; it therefore functions as a undirectional block on expression and social advancement. No theoretical discourse on the dignity of all cultures will really compensate for the fact that, for a ‘Black’ in Britain or a ‘Seur’ in France, the assimilation demanded of them before they can become ‘integrated’ into the society in which they already live (and which will always be suspected of being superficial, imperfect or simulated) is presented as progress, as an emancipation, a conceding of rights. And behind this situation lie barely reworked variants of the idea that the historical cultures of humanity can be divided into two main groups, the one assumed to be universalistic and progressive, the other supposed irremediably particularistic and primitive. It is not by chance that we encounter a paradox here: a ‘logically coherent’ differential racism would be uniformly conservative, arguing for the fixity of all cultures. It is in fact conservative, since, on the pretext of protecting European culture and the European way of life from ‘Third Worldization’, it utopianly closes off any path towards real development. But it immediately reintroduces the old distinction between ‘closed’ and ‘open’, ‘static’ and ‘enterprising’, ‘cold’ and ‘hot’, ‘gregarious’ and ‘individualistic’ societies – a distinction which, in its turn, brings into play all the ambiguity of the notion of culture (this is particularly the case in French!).

The difference between ‘cultures, considered as separate entities or separate symbolic structures (that is, ‘culture’ in the sense of Kultur), refers on to cultural inequality within the ‘European’ space itself or, more precisely, to ‘culture’ (in the sense of Bi/dung, with its distinction between the academic and the popular, technical knowledge and folklore and so on) as a structure of inequalities terrdentially reproduced in an industrialized, formally educated society that is increasingly internationalized and open to the world. The ‘different’ cultures are those which constitute obstacles, or which are established ‘as obstacles (by schools or the norms of international communication) to the acquisition of culture. And, conversely, the ‘cultural handicaps’ of the dominated classes are presented as practical equivalents of alien status, or as ways of life particularly exposed to the destructive effects of mixing (that is, to the effects of the material conditions in which this ‘mixing’ occurs).[x] This latent presence of the hierarchic theme today finds its chief expression in the priority accorded to the individualistic model (just as, in the previous period, openly inegalitarian racism, in order to postulate an essential fixity of racial types, had to presuppose a differentialist anthropology, whether based on genetics or on Volkerpsychologie): the cultures supposed implicitly superior are those which appreciate and promote ‘individual’ enterprise, social and political individualism, as against those which inhibit these things. These are said to be the cultures whose ‘spirit of community’ is constituted by individualism.

In this way, we see how the return of the biological theme is permitted and with it the elaboration of new variants of the biological ‘myth’ within the framework of a cultural racism. There are, as we know, different national situations where these matters are concerned, The ethological and sociobiological theoretical models (which are themselves in part competitors) are more influential in the Anglo-Saxon countries, where they continue the traditions of Social Darwinism and eugenics while directly coinciding at points with the political objectives of an aggressive neo-liberalism.[xi] Even these tendentially biologistic ideologies, however, depend fundamentally upon the ‘differentialist revolution’, What they aim to explain is not the constitution of races, but the vital importance of cultural closures and traditions for the accumulation of individual aptitudes, and, most importantly, the ‘natural’ bases of xenophobia and social aggression, Aggression is a fictive essence which is invoked by all forms of neo-racism, and which makes it possible in this instance to displace biologism one degree: there are of course no ‘races’, there are only populations and cultures, but there are biological (and biophysical) causes and effects of culture, and biological reactions to cultural difference (which could he said to constitute something like the indelible trace of the ‘animality’ of man, still bound as ever to his extended ‘family’ and his ‘territory’), Conversely, where pure culturalism seems dominant (as in France), we are seeing a progressive drift towards the elaboration of discourses on biology and on culture as the external regulation of ‘living organisms’, their reproduction, performance and health. Michel Foucault, among others, foresaw this.[xii]

It may well be that the current variants of neo-racism are merely a transitional ideological formation, which is destined to develop towards discourses and social technologies in which the aspect of the historical recounting of genealogical myths (the play of substitutions between race, people, culture and nation) will give way, to a greater or lesser degree, to the aspect of psychological assessment of intellectual aptitudes and dispositions to ‘normal’ social life (or, conversely, to criminality and deviance), and to ‘optimal’ reproduction (as much from the affective as the sanitary or eugenic point of view), aptitudes and dispositions which a battery of cognitive, socio psychological and statistical sciences would then undertake to measure, select and monitor, striking a balance between hereditary and environmental factors, ” In other words, that ideological formation would develop towards a ‘post-racism’. I am all the more inclined to believe this since the internationalization of social relations and of population movements within the framework of a system of nation-states will increasingly lead to a rethinking of the notion of frontier and to a redistributing of its modes of application; this will accord it a function of social prophylaxis and tie it in to more individualized statutes, while technological transformations will assign educational inequalities and intellectual hierarchies an increasingly important role in the class struggle within the perspective of a generalized techno-political selection of individuals. In the era of nation-enterprises, the true ‘mass era’ is perhaps upon us.

[i] It was only after writing this article that Pierre-Andre Taguieffs book, La Force du prejuge. Essai sur Ie racisme et ses doubles (La Decouverte, Paris, 1988), became known to me. In that book he considerably develops, completes and nuances the analyses to which I have referred above, and I hope, in the near future, to be able to devote to it the discussion it deserves.

[ii] Colette Guillaumin has provided an excellent explanation of this point, which is, in my opinion, fundamental: ‘The activity of categorization is also a knowledge activity…Hence no doubt the ambiguity of the struggle against stereotypes and the surprises it holds in store for us. Categorization is pregnant with knowledge as it is with oppression.’ (L ‘Ideologie raciste. Genese et langage actuel, Mouton, Paris/The Hague 1972, pp. 183 et seq.)

[iii] L. Poliakov, The Aryan Mylh: A History of Racisl and Nationalist Ideas in Europe, transl. E. Howard, Sussex University Press, Brighton 1974; La Causalile diabo/ique: essays sur /’origine des persecutions, Calmann-Levy, Paris 1980.

[iv] Compare the way in which, in the United States, the ‘Black problem’ remained separate from the ‘ethnic problem posed by the successive waves of European immigration and their reception, until, in the 1950s and 60s, a new ‘paradigm of ethnicity’ led to the latter being projected on to the former (d. Michael Omi and Howard Winant, Racial Formation in the United Slates, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, 1986).

[v] See in particular his ‘Les Presuppositions definitionnelles d’un indefinissable: Ie racisme’, Mots, no, 8, 1984; ‘L’ldentite nationale saisie par les logiques de racisation. Aspects, figures et problemes du racisme differentialiste’, MOIS no, 12, 1986; ‘L’ldentite franiWaise au miroir du racisme differentialiste’, Espaces 89, L ‘i’Eienlile franfaise, Editions Tierce, Paris 1985. The idea is already present in the studies by Colette Guillaumin, Sce also Veronique de Rudder, ‘L’Obstacie culturel: la difference et la distance’, L ‘Homme et la sociele, January 1986. Compare, for the Anglo-Saxon world, Marrin Barker, The New Racism: Conservatives and the ldculogy of the Tribe, Junction Books, London 1981

[vi] This was a lecture written in 1971 for UNESCO, reprinted in The View from Afar, transl. J. Neugroschel and P. Hoss, Basic Books, New York 1985; Cf, the critique by M. O’Callaghan and C. Guillaumin, ‘Race et race.,. la mode ‘naturelle’ en sciences humaines’, L ‘Homme el la societe, nos 31-2, 1974. From a quite different point of view, Levi-Strauss is today attacked as a proponent of ‘anti-humanism’ and ‘relativism’ (cf. T. Todorov, ‘Levi-Strauss entre universalisme et relativisme’, Le Debal, no. 42, 1986; A. Finkielkraut, La Defaile de la pensee, Gallimard, Paris 1987). Not only is the discussion on this point not closed; it has hardly begun. For my own parr, I would argue not that the doctrine of Levi-Strauss ‘is racist’, but that the racist theories of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries have been constructed within the conceptual field of humanism; it is therefore impossible to distinguish betWeen them on the basis suggested above (see my ‘Racism and Nationalism’, this volume, pp. 37-67).

[vii] In Anglo-Saxon countries, these themes are widely treated by ‘human ethnology’ and ‘sociobiology’. In France, they are given a directly culturalist basis. An anthology of these ideas, running from the theorists of the New Right to more sober academics, is to be found in A. Bejin and J. Freund, eds, Racismes, anliracismes, Meridiens-Klincksieck, Paris 1986, It is useful to know that this work was simultaneously vulgarized in a mass circulation popular publication, J’ai lOut compris, no. 3, 1987 (‘Dossier choc: lmmigres: demain la haine’ edited by Guillame Faye).

[viii] Ruth Benedict, among others, pointed this out in respect of H. S. Chamoerlain: ‘Chamberlain, however, did not distinguish Semites by physical traits or by genealogy; Jews, as he knew, cannot be accurately separated from the rest of the population in modern Europe by tabulated anthropomorphic measurements. But they were enemies because they had special ways of thinking and acting. “One can very soon become a Jew…” etc.’ (Race and Racism, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London 1983 edn, pp. 132 et seq.). In her view, it was at once a sign of Chamherlain’s ‘frankness’ and his ‘self-contradiction’. This selfcontradiction became the rule, but in fact it is not a self-contradiction at all. In antiSemitism, the theme of the inferiority of the Jew is, as we know, mucl) less important than that of his irreducible otherness. Chamberlain even indulges at times in referring to the ‘superiority’ of the Jews, in matters of intellect, commerce or sense of community, making them all the more ‘dangerous’. And the Nazi enterprise frequently admits that it is an enterprise of reduction of the Jews to ‘subhuman status’ rather than a consequence of any de facto subhumanity: this is indeed why its object cannot remain mere slavery, but must become extermination.

[ix] See this volume, chapter 3, ‘Racism and Nationalism’.

[x] It is obviously this subsumption of the ‘sociological’ difference between cultures beneath the institutional hierarchy of Culture, the decisive agency of social classification and its naturalization, that accounts for the keenness of the ‘radical strife’ and resentment that surrounds the presence of immigrants in schools, which is much greater than that generated by the mere fact of living in close proximity. Cf. S. Boulot and D. BoysonFradet, ‘L’Echec scolaire des enfants de travailleurs immigres’, Les Temps modernes, special number: ‘L. ’lmmigration maghrebine en France’, 1984.

[xi] Ct. Barker, The New Racism.

[xii] Michel Foucault, The History of Sexuality, vol. I, An Introduction, transl. Robert Jurley, Peregrine, London 1978.

This essay seeks to offer some very tentative and provisional hypotheses by way of establishing the inter-connections amongst such phenomena as war, population movement and formation of state system in South Asia. While individual studies focusing on any one of these phenomena are available, studies articulating them into a common frame of reference are not only rare, but almost non-existent. The importance of such a common frame can hardly be denied: On the one hand, it draws our attention to the necessity of appreciating them in their combination rather then in isolation from each other and makes them an indispensable part of contemporary political inquiry. On the other hand, it also serves as a convenient point of departure for many of the future researches that might be interested in working on the hypotheses enumerated here. Viewed in this light, the present essay is only a preliminary attempt at deciphering their inter-connections within a common frame of reference.

The task is not easy; for one thing there is no simple and foreordained way of understanding their inter-connections. The commonplace belief that modern wars are of such a scale and magnitude that they necessarily result in massive demographic displacements whether within the country or across it does not exactly hold true in a region like South Asia. Or even if it does, it certainly does not in the same manner, as is the case in other parts of the world. Contrary to popular expectations, large-scale population movements from one country to another especially after partition could not give birth to demographically homogeneous nations either in India or in Pakistan. Now with the benefit of hindsight and of course at great cost, we are slowly realizing that no amount of population movement – however gigantic and long-drawn that be, would ever contribute to such homogeneous and seamless nations and cleanse them of ethnic minorities. For another, we have also to recognize that any understanding of how these phenomena are inter-connected requires to be qualified by what I would call, an among-other-things rider. Thus, when we argue that the connection between war and population movement is so complex that the former sometimes follows the latter instead of preceding and catalysing it – as was the case in 1971 war, we have to take account of a plethora of factors which in conjunction with that of population movement presumably due to a prolonged spell of civil war in the then East Pakistan, had triggered off the Indo-Pak war and led to the liberation of Bangladesh.

War and War-like Situations

Before we make any further headway, it may be instructive to sound at least two methodologically important caveats.

First, wars, especially those of South Asia, give unto themselves not just one but many “histories”. As one raises this issue, one obviously reminds oneself of how the “official” history of Pakistan interprets them and how it is – to understate the point, at variance with its Indian counterpart. Besides, there is no reason to accept that the official history of whatever country is the only available uncontested history within the country – that can throw all other narratives from out of existence. What is authenticated as the official history of war is seen to be constantly engaged in a war of attrition with a multiplicity of histories that narrate the wars in their own characteristic ways. By way of engaging with the official history, they tend to assert their right to be different from it. The point has two implications. The first implication is that, these little narratives influence population movements as much as they are influenced by official histories. While exploring the possibility of writing an alternative history of two Bengals, Sudhir Chakrabarty in his inimitable style noted how the space of the Lalan (a famous Sufi saint of the nineteenth century) cult in central Bengal cut across the international boundaries drawn as a result of partition. About ten followers of the same cult belonging to Betai village of the district of Nadia now in West Bengal decided to cross the international boundary in 1955 without of course the valid papers that were and are still needed to cross it, in order to visit the holy samadhi (burial site) of the great saint located in the-then East Pakistan. They were subsequently arrested and taken into custody by the Pakistani authorities for having tried to violate the international boundary. This is an instance of how the notion of an alternative space runs parallel to the internationally defined space of nation-states and force the latter to compete with it.[1] The second implication is that, we may say that the role of little narratives in the formation of state-system can hardly be underestimated. It is for instance suggested that the formation of a state implies the appropriation and in its wake complete obliteration of the little narratives under reference. This “fundamentally imperial structure” of the state ideology in the words of Dipesh Chakrabarty, “never described the actual political practice in India where religious idioms and imagination had always been strongly present”.[2] To my mind, the problem is much more complicated than what the scholars of state formation would have us believe. It has to do with the larger question of allowing the state to come to terms with and if necessary, to accommodate these little narratives. The unities of the state discourse are now ruptured in a way that they have lent to the little narratives a hitherto unprecedented freedom of playing a critical role in constructing the official narrative and in bringing them to bear on it. State’s discourse is more a constellation of these forces than their complete obliteration. It is as we shall have occasion to see, much more porous and loose-ended than what the prevalent theories of state formation take it to be.

Secondly, histories of war and histories of peace are not separate or for that matter separable. They are deeply inter-woven in the sense that there seems to be a vast twilight zone comprising what may be called, war-like situations that cannot be clubbed together with either of the two above-mentioned categories. It is necessary to introduce this category into our frame of reference for they play an important role – much more important than that of war in setting off population movements in South Asia. Both the irreducibility of little narratives and the problematic nature of war and peace make it imperative on our part to decipher the inter-connections among war, population movement and state formation in a primarily interpretative way rather than in any strictly empirical way. Where the world of wars is constituted in a problematic manner and gives unto itself many histories than one, we can only hope to make sense of them with the help of our own interpretation, that is to say, with our own way of `worlding’ the world of wars. The exercise cannot but be interpretative.

While wars in history have attracted a good number of philosophers starting from Thucydides down to let us say, Chris Hables Gray whose Post-Modern Wars has created a sensation since its publication in 1997, Clausewitz’s definition of it still serves as the only viable point of entry into the subject. As he points out: “War is…an act of force to compel our enemy to do our will”.[3] Viewed in this perspective, wars and war-like situations are divergent from each other on at least three major counts: First, the force employed in times of war is self-spiralling in character. Clausewitz for instance argues: “If one side uses force without compunction, undeterred by bloodshed it involves, while the other side refrains, the first will gain the upper hand. That will force the other to follow suit; each will drive its opponent toward extreme, and the only limiting factors are the counter-reprisals inherent in war.”[4] In war-like situations also, one definitely compels another “to do one’s will” given that there is a unitary will of the sort that Clausewitz has in mind, without “driving another to the extreme”. A country while inciting and perpetuating war-like situations in another chooses not to “drive another to the extreme” because it is not willing to risk the reprisals for interests which in its perceptions are not too fundamental to warrant a full-blown war. Or it may be that the interests are considered to be fundamental but war-like situations are preferred to wars as a means for attaining them. Sumit Ganguly for instance makes the point that even in times of hot Indo-Pak wars, mutual understanding and diplomatic communication were never lost.[5] That a country is not willing to push its adversary to the extreme and is intent on keeping the exercise of violence within a tolerable threshold does not mean that war-like situations are less effective instruments of a country’s foreign policy. In fact, such wars as Chris Hables Gray argues, have in a large measure been successful in calling the triumphalism of the West into question (“What makes this war so important is that it reversed the hundreds of European victories”)[6], and establishing the superiority of oriental technologies like, people’s war to western technologies and cyber-war.

War according to Clausewitz, is a conflictual engagement between two “whole” communities with respective “wills” pitted against each other. One wonders whether such fully formed, homogeneous communities with their fragments knit into seamless wholes, with their wills sharply different from each other ever exist – or to say the least, pre-exist the outbreak of wars even in advanced western democracies. For wars in South Asia have also been principal vehicles of organizing peoples into fairly homogeneous nations. As Ainslie Embree informs us, “The 1962 war with China was a turning point in defining India as a nation. Nehru spoke of it as a blessing in disguise because internal disunity had been swept aside by the Chinese threat and the new mood could be used to achieve industrial advances as well as military preparedness.”[7] War-like situations on the contrary imply that there may remain some fragments within what the state claims to be parts of its national body that simply refuse to be regarded as its constituent parts and join the state’s preparations for coping with them. Such fragments reflect the limits of a state’s nationhood and are seen to act at times at the behest of the enemy country. Hence, while coping with war-like situations, a state has to wage a war with its fragments.[8] Classical political theory also tells us that a citizen’s attachment to the national body particularly in times of war is to be regarded more as an end in itself than a means to an end. Machiavelli for instance, contended that wise princes would prefer to “lose battles with their own forces than win them with others in the belief that no victory is possible with alien arms”.[9] That is why, his Prince underlines time and again the importance of the natives in the army structure who are likely to fight wars unto the last without asking why and whose obeisance to the nation is both unflinching and unwavering. On the other hand, a nation during war-like situations especially in South Asia reportedly includes many fragments whose attachment to it hardly contains any intrinsic worth. They consider themselves to be a part of the nation only so long as their attachment fulfils certain interests particular, if not peculiar to themselves. While referring to the “border people” who have migrated to West Bengal from Bangladesh, Ranabir Samaddar argues that for them, citizenship is very like an ordinary commodity that is freely bought and sold, in one word, transacted without any sense of moral piety, depending on the mutual interests of the parties involved in it in a world that according to him, is completely demoralized: “Citizenship has come to such a state, it means not membership of a political community, but one end of a transactional relation”.[10]

Thirdly, Clausewitz makes a clear distinction between force and political will. Although it is true that force at times especially during wars has a tendency to “usurp” political will, ideally it should be employed in order to implement the latter rather than anything else. Clausewitz’s definition not only contains a strong rationalist tinge whereby force is made subordinate to will but also in the same vein sensitizes us to such situations where wars might verge on the irrational and use of force might look senseless with no apparent political will to be implemented. War-like situations serve as glaring instances where the Clausewitzean distinction between force and political will is blurred – if not already vanished, for in this case there seems to be no political will other than and independent of the use of force. A country that is keen on imposing such situation on another becomes successful and fulfils its objective the moment it imposes it, for it thereby secures a certain disarming of its enemy – one of the chief objectives of war, by way of compelling it to keep a substantial part of its armed troops busy with maintaining law and order inside the country. According to one conservative estimate, India had committed a quarter million of its armed troops to quelling armed insurrections in the former princely state of Jammu and Kashmir. War-like situations are like self-evident truths in the sense that there is no hidden truth beyond what is self-evident to us.

Several imageries of war are in currency to refer to war-like situations. Some of them are – proxy wars, (un-)civil wars and low-intensity conflicts. Conversely, India has engaged in four wars of varying degrees of intensity since 1947 – three of which have been with Pakistan. As Sumit Ganguly, widely acclaimed as an expert on Indo-Pak wars, maintains, “While many people quibble over definitions of war, it is safe to say that by any reasonable standard there were three wars between India and Pakistan between 1947 and 1971”.[11] Wars are episodic or to borrow a Clausewitzean expression “single-short blows”, but war-like situations are embedded in the state’s regime of the normal.[12]

War-like Situations and Population Movements

None of the wars mentioned above, has resulted in any major trans-border population movement. None of the twelve major bilateral population movements outlined in Myron Weiner’s study published in 1993 – excepting only one, “the flight of Bangladeshis to India” had to do directly with war – precisely, the Indo-Pak wars.[13] In this case too, war did not precede but followed the massive population influx from the-then East Pakistan to India, though of course there was a considerable return migration immediately after the war which helped India in securing at least the semblance of a demographic balance within a short while.

At this juncture, we must make a distinction – albeit of conceptual nature, between two kinds of population movements – one induced by war and the other by prolonged spell of war-like situations. First of all, the probability of return migration is as we have already noted, always higher in cases of war than in that of war-like situations. Since the latter often masquerade as the normal, they are of enduring nature and do not seem to create an atmosphere conducive to the migrants’ forthwith return to their homes. Secondly, the country that receives the immigrants in times of war usually keeps a close watch on their movements, scrupulously counts their numbers as far as practicable, sometimes recognizes them as refugees in need of some special treatment, seeks to herd them together in sufficiently secluded camps so that they do not disappear into the faceless and lonely crowd called, nation, that it claims to enclose and represent and most importantly, garner international support in their favour with of course a varying degree of success. During Bangladesh crisis for instance, other countries assumed nearly one-fourth of the estimated costs of supporting the refugees in camps and virtually none of the costs for the larger number who had found sanctuaries outside the camps. The figure reached 9.8 million at its peak and out of it approximately 3 million did not choose to go the state-run relief camps. Richard Sisson and Leo Rose, have argued that in spite of state’s attempts at isolating them and re-locating them to some far-off parts of the north-east, they posed a major burden to the nation’s exchequer and to the economy as a whole.[14] But whatever the state does as part of its humanitarian programme concerning the refugees, it never allows the distinction between its citizens and foreigners to be blurred and obliterated. The making and maintaining of such distinction is always considered to be crucial to the state’s nation-building project. But since much of the immigration that takes place during war-like situations are of illegal and clandestine nature, it goes on undetected and at times it becomes difficult – if not impossible on the part of the receiving country to see to it that they do not get mixed up with the faceless multitude of the nation.[15] State’s failure in making and maintaining the distinction has sparked off at least two mutually opposite kinds of social reactions. On the one hand, there are attempts on peoples’ part (as was the case during the Assam movement of 1979-1985) at making the state do what it does not otherwise do, that is to say, build the nation. What the state might do is not to keep a watch on the illegal entrants from across the borders for that is quite impossible, but to keep a count on its own citizens and thereby lend to the nation a face that has hitherto remained faceless and anonymous. Voters’ identity cards and citizenship certificates are some of the markers that are meant for separating the citizens from the foreigners. A modern state cannot do without “enumerating” its people into a closely-knit and measurable nation.[16] On the other hand, the state’s insistence on making and maintaining this distinction creates panic in the minds of some communities whose identity as Indian citizens is to say the least, ambiguous. The movement of the Gorkha National Liberation Front under the leadership of Mr. Subash Ghisingh in Darjeeling (West Bengal) for their certification as Indians serves as a case in point.

Thirdly, wars in South Asia have invariably centred on the territorial question. In other words, they were fought with motives other than dumping a country’s surplus population on another country. In none of the four wars excepting that of 1971, have the population movements been too significant to cause an alarm. Conversely, war-like situations are sometimes created and perpetrated with the motive of conveniently dumping the excess population on another with the advantage of remaining unrecognised by the receiving country. It is for instance argued that the civil war in pre-war East Pakistan was a means, resorted to by the Pakistani state, of making section of its people mostly consisting of the Bengali Hindus leave the country and easing out the excess population constantly posing a danger to the country’s economy and “Islamic” culture. Indeed, a theory of lebensraum though expressly denied by the Bangladesh state, is catching fast the imagination of the Bangladeshi intelligentsia. For instance, an eminent professor of Dhaka University has reportedly argued that tremendous population pressure is bound to take the country to the road to inevitable disaster in near future and unless the people of Bangladesh are permitted to spread out to such vast and of course sparsely populated tracts of land that just lie across her north-eastern and south-eastern borders comprising a substantial part of north-eastern India and the Arakan Hills of Myanmar, Bangladesh would not be able to withstand the imminent disaster.[17]

State System and State Discourse

The term state-system may be used in two relatively distinguishable senses. In the macro sense, it may be understood to mean the complex web of inter-linkages amongst different nation-states of South Asia and the inter-linkages are so intimate that “each acknowledges and to some extent guarantees others’ existence”. The closest approximation to such a system is the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC). In the strict sense, one wonders whether SAARC can be taken as an illustration of such a system for one notices here nations that acknowledge and guarantee – only grudgingly, if at all, each other’s existence. The survival of Pakistan as a sovereign state depends on an explicit negation of the principles that lay down the foundations of the Indian state. The reverse is also true. In the micro sense, it refers to a process whereby a state with its intricately woven network of political institutions gets itself formed. Charles Tilly’s The Formation of National States in Western Europe is still regarded as an excellent exposition of formation of state systems in Western Europe. The opening essay underlines four diverse processes implicit in the project of state formation – territorial consolidation, centralization, differentiation and monopolization of the legitimate means of force and coercion. It means over and above, the establishment of a central political authority that is sufficiently differentiated from the prevailing social groups – ethnic and non-ethnic, enjoys a virtual monopoly over the legitimate instruments of coercion and the writ of which extends over the entire territory that it lays claim to. While Tilly’s definition has a strong institutional bias, it does not adequately maks us sensitive to the discourse that informs and under-girds whatever the state does by way of institutionalising itself.

The concept of state discourse has at least four significant implications that may be discussed at this point. First, what it does is to privilege those who adhere to it and to incorporate them into the national body as its “natural” constituents. By the same token, it also excludes those who do not or may be, who refuse to acquiesce to the discourse and urges them – not always implicitly, to vacate the territory that it claims to consolidate into a nation or to stay in it as ethnic minorities with an attendant denial of their rights which they consider to be fundamental to their survival as distinct cultural communities. The state discourse thereby facilitates the process of “natural” selection.[18] Partition and in its wake the birth of two nation-states in South Asia have given the people an opportunity of being “naturally” enclosed by either of the two state discourses antagonistic to each other. The opportunity also conferred on them an obligation – of making up their minds. They could not do without joining either of the two nation-states. Political geography of modern nation-states hardly leaves room for those who would like to be identified with units – larger or smaller than those of the nation-states. Hiranmoy Bandyopadhyay in a book written in an intimate, semi-autobiographical style has cited more than a dozen instances where Bengali-speaking Muslims of post-partition West Bengal thought it unethical on their part to stay on even after the birth of a separate Muslim state.[19] When state discourse grips the masses, it does not have to exercise force in order to make the territory homogeneous. The more it rules by discourse, the less it feels the necessity of resorting to force and coercion.

In this connection, it may be pointed out that citizens’ attachment to a state may be either of the two polar types or any combination of them: transactional and natural. In the first case, people who are to be incorporated into the national body are first of all assumed as outsiders whose entry into it depends on a bargain that they have to strike with the concerned state or vice versa. The relationship between the state and its people in this instance is evidently of contractual or transactional nature. The state normally does not quite encourage people to enter into a relationship of this sort partly because it is expensive as the state has to deliver what Packenham once called, “political goods” like, law and order, life, liberty and pursuit of happiness etc., and partly because peoples’ loyalty to the state in this case is of fragile and vacillating nature. As soon as the state stops for whatever reasons, delivering the goods, loyalty is or at least is threatened to be withdrawn. It is for this reason that the state always chooses to translate the first kind into the second one. In this instance, peoples’ association with the state is taken to be too tacit to be actively demonstrated. This as we will see later, lends to the discourse an element of unchallengeability. M.J. Akbar’s India – The Siege Within may be regarded as a text that accepts Kashmir’s inclusion in India as an accomplished and irreversible fact and thereby keeps the question beyond the realm of negotiation. This text helps in sanitizing the issue and robs it of its problematic character. At the same time, it is a classic illustration of a paranoid text that accuses Pakistan and other vested interests of problematizing the issue and transforming it into a question.

Secondly, our emphasis on the state discourse enables us to appreciate its distinction from the otherwise widely used term – nationalist discourse. The post-modernist critique has called the state’s claim to enclose and represent a nation into question and has drawn our attention to the challenges that it faces while building the nation both from within and also from without. Some of the fragments the state considers to be organic to the national body are increasingly questioning the assumptions that aim at assimilating them into it and depriving them of the right to retain their cultural identities. Similarly, alongside these sub-national fragments, there are also trans-national centres of power – sometimes represented by other sovereign states which not only context the particular state’s unilateral claim over the national body but stake their own claims over it. When both these forces work together, they pose a potent threat to the state. The nation in other words, has become a contested site. In that sense, the concept of state discourse confines our attention to what the state does and thereby frees us from the obligation of characterizing its activities as necessarily nationalist. Thirdly, our distinction between state formation and state discourse instructs us to keep the opposition to the latter clearly distinct from the cases where the institutional prerequisites of the state are under attack. Such a distinction is necessary for “the new revolutionaries are concerned not so much about the political structure of the nation-state as they are about political ideology that under-girds it”.[20] It is for this reason that the concept of state discourse has acquired some prominence in recent years.

Fourthly, the concept is inseparably connected with that of modernity. We may even say that they advent of modernity has bestowed on the state the responsibility of holding on to and elaborating a discourse. A brief comparison of the process of state formation in modern India with that in pre-modern times may be instructive at this point. Since a plurality of states existed within a more or less culturally contiguous geographic space, any expansion, contraction or even annihilation of state’s borders did not necessarily lead to any significant migration of population from one place to another in pre-modern India.[21] This does not mean that there was no migration whatsoever in pre-modern India. Migration to be precise was sparked off by factors other than the modification and transformation of political boundaries. Peasant migration within the larger Gangetic plains of undivided Bengal was a very common feature even during the colonial rule. In other words, the state did not have to elaborate a discourse; it was in the words of Rudolph and Rudolph, “an instrument for upholding and protecting the society and its values'”[22] As a consequence, the cultural order of the society was not severely disrupted and the people did not feel it imperative to move over from place to place once the changes in state’s boundaries came into effect. In sum, political changes would hardly touch upon the society and its values. As modernity encourages the states to organize their territories into culturally enclosed spaces and enumerate their peoples into tightly-knit, homogeneous nations, it also feels the necessity of clinging to and elaborating a discourse that as we have already argued, facilitates “natural” selection. That people are migrating from Bangladesh to the bordering states of India reveals that they could not qualify the process that the Bangladeshi state has set for its nation. Increasing Islamization, sharply deteriorating economic conditions, frequent military interventions along with many other factors have made their lives difficult in Bangladesh and push them as it were, to flee the country where they have been living for generations.[23] They are in Myron Weiner’s language, “rejected” people.

War, War-like Situation and the State Discourse

The prevailing literature on Indo-Pak wars looks upon them essentially as conflicts between two “patently antagonistic models” or state discourses as we have termed them. Partha S. Ghosh for instance observes,

These two models (those of India and Pakistan) have not only been mutually incompatible, but having been professed in two contiguous countries with the same socio-historic experience, with no mutual boundaries, and with a record of conflictual relationship that developed immediately after independence over Kashmir, they have become patently antagonistic threatening each one’s basic principles of state policy…Islamic Pakistan and secular India became anathema to each other for the simple reason that the very survival of the states depended on an assertion on precisely those theories which had resulted in the partition, namely, the two-nation theory based on religion versus the one-nation theory based on territorial and historical concept of “Mother India”.[24]

Such a view to my mind, suffers from many shortcomings two of which deserve a special mention at this point. First, it not only exaggerates the mutual antagonism between these two countries, but wrongly assumes that the discourses are fully formed and elaborated well before they take on and confront each other. It also presupposes that the strategies that the adversaries employ against each other in times of war are issued from the discourses that are both given and immutable. According to this view, the Indo-Pak wars fought almost at regular intervals till 1971 have not seemingly played any role in bringing into existence, elaborating, modifying and even transforming their respective discourses. Secondly, and as corollary to the first, this view freezes the discourses at a given point of their evolution – in our case at the point when the subcontinent was partitioned into two sovereign states and is unable to account for the changes that the discourses have undergone since then while adapting themselves to the changing requirements of time. In that sense, both the state discourses had to strive hard for negotiating with the “patent models” or stereotypes which have been generously used to characterize them – “the two-nation theory based on religion” and “the one-nation theory based on territorial and historical concept of Mother India”. Such stereotypes also fix up the limits to states’ spheres of action and negotiation. I propose to illustrate these points with reference to the elaboration of the discourse of the Indian state in course of the three major wars with Pakistan between 1974 and 1971.

The first Indo-Pak war that took place immediately after independence may be conceived of as the moment of contingency in its elaboration: First, India continued to interpret the Kashmir imbroglio with the terms that were directly derived from what is popularly known as, the nationalist discourse crystallized during the struggle against colonial rule since the last century. It was seen primarily – if not exclusively, as an extension of the colonial policy of dividing the Indians and “weakening the new nation and preventing her from becoming a powerful factor in Asia” through the creation of Pakistan. It is interesting to note that Great Britain continued to remain India’s point of negative reference. India took time to recognize Pakistan as her principal adversary. Besides as investigative reports point out, she was not seriously interested in committing herself to any kind of long-term involvement in Kashmir: “If in the normal course, Kashmir had acceded to Pakistan, few in India would have been upset about it…To many in India, the tribal raid was an instance of Pakistan’s arrogance, similar to that displayed by the Muslims before independence, which, if not challenged immediately, would manifest itself even more blatantly in the years to come. What seemed important then…was not the acquisition of territory by India but stopping Pakistan from enlarging its boundaries”.[25] As a counter-factual argument, it has been suggested that had Sheikh Abdullah not asked for India’s military assistance at that crucial hour in fighting the raiders, India in all probability would not have been involved in what ultimately turned out to be an endless war. But once she committed herself, there was no going back and her discourse bore the imprints of the involvement in a way that proved to be inerasable. What was then dismissed as too contingent a factor to engage our sustained attention came to occupy a central position in the State’s scheme of things and became the be-all-and-end-all of our national identity.

The war of 1965 may be interpreted as the moment of trial not of course in the ordinary sense of “the one-nation theory based on territorial and historical concept of Mother India” being pitted against “the two-nation theory based on religion”, but in the deeper sense that the Indian state found it extraordinarily difficult to remain steadfast to what it had decided to embrace – “the one-nation theory” itself. The war had conferred on the state the special responsibility of holding it accountable to a theory that admittedly transcended the religious and communal differences and was believed to have consolidated its citizens into the generic community of Indian nation. The depreciation of this theory was so blatant and spectacular in the everyday political practice that the state was not only busy with confronting an external enemy on the warfront but grappling with the responsibility that the rhetoric of one-nation theory has assigned to it. The Indian state was passing as it were through a particularly schizophrenic state in which more than being engaged in a war with an external enemy, it had to come to terms with what it held to be its true moral self. The transformation of “a low-key, amorphous, tolerant and peculiarly consensual nationalism” into a highly monochromatic form which was out to throttle and emasculate the cultural diversities and steamroll them into one homogeneous type at about the same time had turned the discourse by its head and constantly reminded us that no amount of political reconstruction would be able to bring the discourse to the line of actual political practice and vice versa. The state was caught up in a terrible political dilemma: It could neither discard nor stand up to the rhetoric of one-nation theory. Besides, the minorities’ natural concern for their communities located just across the borders was stigmatised as flagrantly anti-national. As Ayesha Jalal writes, “Indian Muslims have had to distance themselves from any display of concern about their predicament across the border”.[26] Even M.J. Akbar notes that with Nehru’s demise, “the communal Hindu element in the power structure could not be kept under control”.[27] He makes a particular reference to the anti-Sikh agitation in which several communal organizations came together and joined their hands in forcing the state to assume a monochromatic form.

According to Sumit Ganguly, the war of 1965 proved beyond any doubt that “there was no ground swell of support for Pakistan’s claim on Kashmir amongst the Muslim population of the state”.[28] It is interesting to see how in spite of the two wars, the state discourse of India could retain its popularity even amongst the Muslims of the state. It was the promise of “secularism and socialism”‘ held out by the discourse rather than the actual political practice, that played a key role in attracting the Sheikh and his people to veer towards India. As Sheikh Abdullah is reported to have said, “…We have joined India because of its ideal – secularism and socialism. India wanted to build a state where humanism would prevail. So long as India sticks to these ideals, our people have a place nowhere else but in India”.[29] It seems that they were still prepared to give India what in juridical language may be called, a benefit of doubt and more significantly a chance to prove before the world as well as herself that her political practice was worthy of the promise embedded in the discourse.