RESEARCH AND ORIENTATION WORKSHOP ON FORCED MIGRATION

Winter Course on Forced Migration, 2007

Offered by CRG A Centre of Excellence

A Report On The Fifth Winter Course on Forced Migration 2007

The report is a product of notes and writings prepared by the participants, faculty members and members of the CRG desk for the Winter Course on Forced Migration. Thanks are to the participants and all others who contributed to it. Thanks are in particular to the UNHCR, the Brookings Institution, Government of Finland and Panos South Asia whose generous help and advice made the programme possible.

Contents

1. A Unique Programme

2. Structure of the Course

3. The Participants

4. Members of the Faculty and Speakers at Roundtables

5. Partnerships: Supporting and Collaborating Institutions

6. The Course Schedule

7. Distance Education: Modules and Assignments

8. Creative Assignments

9. Field Visit

10. Public lectures

11. Three day Media programme (Film Screenings, Photo- exhibition and a day long workshop)

12. Workshops, Roundtables and Panel discussions

13. Inaugural and Valedictory Sessions

14. Evaluation

15. Follow –up Activities

16. A day with CRG in Kolkata

17. CRG Team on Forced Migration

18. Advisory Committee

The significance of a human rights and peace education programme on the inter-linked phenomena of massive forced migration, racism, and xenophobia cannot be underestimated in the current political, social, and cultural climate of India, South Asia, and the world in general. There has been an increase in attacks on civilians, atrocities on individuals and groups mostly belonging to minority communities, public espousal of national chauvinism, sexism, and masochism, intolerance, majoritarianism, and wars and war hysteria. The scenario is marked by less tolerance, increase of hatred against foreigners, immigrants and refugees, a reduction of the civic-cultural space for discussion, debate, and dialogue in a context dominated by globalisation and a concomitant reduction of capacity of the states to listen to public voice for democracy, tolerance, and inter-cultural understanding. The situation is compounded by two trends: on one hand, education is becoming more nationalistic, majority-centric, consumerist, and is littered with hate-words and hate-speech, which impact on mass culture and reinforce the mass populist basis of war and militarism; on the other hand, there is a general decline of human rights standards, erasure of human rights protection mechanisms, and an increasing contempt and derision for appeals to heed to human rights laws and humanitarian laws in public life and follow the ethics of considerations for vulnerable sections of society. Never before in this region was there such dire need to work for peace education that would be based on the ethos of culture of peace so as to foster respect for human rights.

Population displacement has taken alarming proportions and has become most conspicuous in recent times due to conflicts, developmental policies, environmental hazards and climate change, and the victims of forced displacement are becoming targets of xenophobic frenzy, inter-state rivalry, suspicion, and hate speech and hate acts. The flows are of mixed and massive types calling for greater attention to human rights standards and humanitarian protection – across boundaries and within nation-states. In short, the situation calls for greater mobilisation of the civic-political space, of human rights, peace, and humanitarian institutions and activists, greater dialogue among all concerned on the related issues of rights, justice, and protection.

Developed through last few years as a programme on human rights and peace education, the annual winter course on forced migration organised each year by the Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group (CRG) has come to be recognised in the region of South Asia as one of the most well known educational programmes on issues of rights and justice relating to the victims of forced migration. In the from of a certificate course, certified by the UNHCR and supported by the Government of Finland and the Brookings Institution, the winter course is aimed at scholars and educationists working on issues of rights and justice, functionaries of humanitarian organisations, national human rights institutions, peace studies scholars and activists, and minority groups, refugee communities, and women’s rights activists. Participants come from all over South Asia, with some joining from Africa, Australia, Europe and the USA. The course attracts a renowned

international faculty, and is now recognised by the National Human Rights Commission in India, and several universities along with various grassroots organisations have collaborated over the years to make it a success.

There are several features of the course, which make it a unique programme. Readers of the report will find the details in subsequent pages; however it is important to summarise them and place them at the beginning:

(a) Emphasis on distance education, its innovation, and continuous improvement through interactive methods, including the use of web-based education;

(b) International standard, rigorous nature of the course, customizing methodologies for forced migration research and generating original research inputs, field work, analysis of the protracted IDP situations, and a comprehensive regional nature of the course;

(c) Emphasis on experiences of the victims of forced displacement in the conflict zones; such as India’s Northeast, Jammu & Kashmir, Andhra Pradesh and Chattisgarh, Bhutan, Sri Lanka and Israel/Palestine;

(d) Special focus on auditing and strategizing media through workshops, film sessions and creative assignments;

(e) Emphasis on gender justice;

(f) Special attention to policy implications;

(g) Follow up programmes such as spreading it to universities, providing inputs to future researchers, innovating local modules, training participants to become trainers of the future programmes;

And, finally building up the programme as a facilitator of a network of several universities, grassroots organisations, Mothers’ Fronts, research foundations, UN institutions etc.

2. Structure of The Course

The Fifth Annual CRG Winter Course on Forced Migration concluded on 15 December 2007. Although this course is called a course on forced migration, it also discusses the root causes for migrations/displacements, and issues such as racism, immigration and xenophobia in the context of displacements. The major thrust area of this course is South Asia although examples from other regions are also brought in for purposes of comparison and analysis. The course, as has already been mentioned earlier, is an outcome of the ongoing and past work by the CRG, and other collaborating groups, institutions, scholars, and human rights and humanitarian activists in the field of refugee studies and on displacement and human rights. The course structure is intended to take cognisance of the gendered nature of forced displacement in South Asia. It pays special attention to victims’ voices and their responses to national and international policies on rehabilitation and care. The course builds on CRG’s ongoing research on forced displacements in the region and hence it is constantly evolving. It analyses mechanisms, both formal and informal, for empowerment of the displaced. It pays particular attention to different forms of vulnerabilities in displacement without creating hierarchies. It is built around eight modules, five of which are compulsory and three others optional. From the three optional modules the participants are expected to select one for their study.

The Compulsory Modules:

· Forced Migration, racism, immigration and xenophobia

· Gender dimensions of forced migration, vulnerabilities, and justice

· International, regional, and the national regimes of protection, sovereignty and the principle of responsibility

· Internal displacement with special reference to causes, linkages, and responses

· Research Methodology in Forced migration Studies

The Optional Modules:

· Resource politics, environmental degradation, violence and displacement

· Ethics of care and justice

· Media and Forced Migration

This year the course activities besides the writing assignments, included workshop and roundtable assignments, group discussions, field visit, creative sessions, review discussions, and face-to-face sessions with resource persons experienced in related areas and with refugees living in camps. The course also included a one-and-half day media workshop and public lectures with participants from other sectors of social life, film and documentary sessions.

Duration and Activities

The course was of three (3) months duration with two and half months duration of distance education, communication on related issues of displacement studies, course assignments by participants and fifteen days of direct course work in the form of a winter workshop. Upon the participants being selected, course material was sent to them in a phased manner. Short introductory note on each module was sent to the participants; along with these notes, lists, bibliographies, and other announcements were also sent. The reading materials were sent to the participants in three phases. For review assignments and term papers, lead questions and discussion points were sent at regular intervals. Each module had a tutor and a number of faculty members. On the basis of the modules chosen by them the participants were encouraged to contact the faculty persons for necessary advice and inputs. Chat sessions were organised so that participants could discuss their assignments with module tutors.

Participants were required to prepare an assignment paper each and bring the papers with them for the workshops where the papers were discussed. These papers were first read and commented upon by the module tutors and then made available for wider circulation and discussion in the CRG website. The participants were also given assignments termed as creative assignment so that the period of three months could also be used for training in communication aspects of humanitarian and human rights work, and other practical aspects such as providing the participants with information and documentation skills, preparing local data base, campaign for fund-raising for human rights and humanitarian efforts, and report writing. Creative assignments were made a mandatory part of the course since 2006 and their results were varied and rich. Participation in the field visit to Malda was also compulsory.

The preparation of course material was of great significance. The course material included mandatory, optional and supplementary materials. The mandatory materials included a number of books, essays and web-based materials. Supplementary materials including one CRG publication on erosion-affected people of Malda for fieldwork were handed to them when they arrived in Kolkata. Three weeks before the participants arrived in Kolkata they were given workshop themes. Each of them was required to participate in one of the workshops. Participants were graded on all these assignments and on the valedictory day these grades were handed to them.

Since 2005 the course also includes two optional modules. In 2007, one compulsory module on ‘Research Methodology in Forced Migration Studies’ and one optional module on ‘Media and Forced Migration’ have been added to the course as per the recommendations of the Advisory Committee meeting held in New Delhi on May 11, 2007. Also, the theme of ‘Global Warming, Climate Change and Forced Migration’ was the special focus of the already existing optional module on ‘Resource Politics, Environmental Degradation, Violence and Displacement’. The participants were asked to select any one of the optional modules of their choice. They were given one assignment from the optional module that they selected. They had to write a review essay analysing some of the reading materials given in that module.

Participants

Twenty-four participants were selected for the course, of whom twenty could complete the course. These participants were selected through public notifications and were drawn from backgrounds of law, social and humanitarian work, human rights work, and academic and research work. Most of them came from South Asia but a few were also from other regions such as Europe, Africa, and Australia and brought forth with them wider experiences of refugee-hood and of rehabilitation and care. Those who could not complete the course were unable to do so mainly due to sudden indisposition and visa problems.

Faculty

The faculty was drawn from people with recognised backgrounds in refugee studies, studies in internal displacement, university teaching and research, humanitarian work in NGOs, legal studies, UN functionaries, particularly UNHCR functionaries; public policy analysis, journalism, and concerned human rights activism and humanitarian work. Attention was paid to diversity of background and region. Importance was attached to the requirements of the syllabus; the faculty was also involved in developing on a permanent scale a syllabus, a set of reading materials, evaluation, and follow-up activities. The resource persons also helped in harmonising the syllabus of this course with the requirements of the participants, and similar syllabi in various universities, workshops, and courses. They graded participants on their skills such as speaking and writing skills, analysis of themes chosen, execution of creative assignments etc.

Evaluation

The participants were evaluated by a number of resource persons. The core faculty evaluated each of their assignments. All the resource persons present evaluated their presentations, including the presentation of their term papers. They were given a grade for the distance education segment and another for the Kolkata workshop. At the end of the course they were given a cumulative grade. The course is equivalent to six credit hours of graduate level work.

The course has a built in evaluation system. Each participant is required to present a written evaluation and each resource person is also expected to do the same. Every year CRG invites independent scholars of renown, social activists and administrators to evaluate the course. This year Professor Rajesh Kharat of Bombay University (Mumbai, India) evaluated the course. Excerpts from their evaluation are presented in Section 14.

Follow-Up

Considering the growing popularity of the course the advisory committee in 2006 asked the CRG organisers to look into possibilities of organizing short courses in collaboration with willing centres and departments of Universities in India as follow-up activity. On the basis of such advice the CRG is now in the process of designing a number of short courses for different Universities and research centres. This year one such course will be held in February 2008 in Hyderabad. A few others are in the pipeline and discussions are being held with some university departments and law schools for holding short-duration courses.

Apart from this a number of workshops on forced migration were held in different parts of South Asia. The CRG also collaborated with a number of institutions and organised a number of public lectures. This year three fellowships were given to the participants of the Winter Course and a delegation of CRG’s senior scholars is expected to visit some centres of advanced learning in Finland. Also CRG conducted many research projects on

the theme of forced migration. Two issues of Refugee Watch (Nos. 28 & 29) – CRG’s flagship journal – were also brought out and became part of the reading material supplied to the participants. The course is also complemented by a series of workshops on internal displacement organized by CRG in different parts of India in 2007. For a detailed report on follow-up activities please read Section 15.

The follow-up activities of the winter course have now assumed the character of an entire programme with other allied work. The course in simple terms has become a round-the-year event developing synergies with human rights bodies and academic institutions. The CRG established the forced migration desk to look after the entire programme.

Anita Ghimire is a doctoral Student in Sociology at the Kathmandu University working on the social and territorial impact of armed conflict induced displacement and the livelihood of Internally Displaced Persons in Nepal.

Ashirbani Dutta is currently working as Project fellow with the University of Calcutta.

Barbara Keller is currently pursuing her Masters at Geographical Institute of the University of Berne.

Elizabeth Williams is working as a research and policy intern with Immigration Advisory Service based in UK.

Elizabeth Snyder is a Professor in International Relations in the University of North Carolina, Ashvellie.

Geetisha Dasgupta is working with Sanbad Pratidin(Robbar), Bengali Newspaper Daily.

Ishita Dey is currently working as a research associate for the Internal Displacement Programme with Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group.

James Ward Khakshi is a community Organizer in Indigenous Peoples’ Development Services (IPDS), a rights based NGO working for Indigenous People in Bangladesh.

Laxmi Shrestha is a Research Officer with the Center for Research on Environment Health and Population Activities (CREHPA), Kathmandu.

Magdalena Sikora is a doctoral student with European University Institute. Her thesis is on law of refugees and internally displaced persons, the implementation of human rights and humanitarian law

Marini De Livera is a lawyer, gender trainer and a human rights activist and is currently working as a National Programme Coordinator with the UNDP, Parliament of Sri Lanka.

Mohinder Singh Yadav is currently DYSP with National Human Rights Commission, India.

Sanam Roohi has completed her masters in Political Science from the University of Calcutta and is currently working as research associate for the Social Justice programme with Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group.

Suranjana Ganguly is currently pursuing her M Phil from IDSK, Kolkata.

Sriram Haridass is working as repatriation Assistant, UNHCR, Sri Lanka.

Tarangini Sriraman is a PhD student of Political Science in University of Hderabad. She is working on Identification documents.

Tiina Kanninen is pursuing her Master’s Degree in International Relations and is working as a part-time editorial assistant for the academic journal Cooperation and Conflict.

Radha Adhikari is the President of the Institute of Gender and Legal Equality, Bhutanese Refugee Organization based in Kathmandu.

Uttam Kumar Das was working with UNHCR Bangladesh as the National Protection/Legal Officer. He has recently joined as the National Programme Officer, International Organization for Migration, Bangladesh.

Walid Kenzari is currently completing his Master’s degree in Political Science at ULB (Free University of Brussels).

James Ward Khakshi is a community Organizer in Indigenous Peoples’ Development Services (IPDS), a rights based NGO working for Indigenous People in Bangladesh.

Laxmi Shrestha is a Research Officer with the Center for Research on Environment Health and Population Activities (CREHPA), Kathmandu.

Magdalena Sikora is a doctoral student with European University Institute. Her thesis is on law of refugees and internally displaced persons, the implementation of human rights and humanitarian law

Marini De Livera is a lawyer, gender trainer and a human rights activist and is currently working as a National Programme Coordinator with the UNDP, Parliament of Sri Lanka.

Mohinder Singh Yadav is currently DYSP with National Human Rights Commission, India.

Sanam Roohi has completed her masters in Political Science from the University of Calcutta and is currently working as research associate for the Social Justice programme with Mahanirban Calcutta Research Group.

Suranjana Ganguly is currently pursuing her M Phil from IDSK, Kolkata.

A.F. Mathew, Faculty, Mudra Institute of Communication at Ahmedabad (MICA), India.

Ariella Azoulay,Faculty of visual culture and contemporary philosophy at the Program for Culture and Interpretation, Bar Ilan University.

Arup Jyoti Das,Coordinator of North East Peoples’ Initiative (NEPI) and a Media fellow of Panos Institute South Asia.

Asha Hans, Director, Sansristi, Bhubaneswar.

A S Panneerselvan,Executive Director, Panos South Asia.

Ashok Swain ,Associate Professor in the department of Peace and Conflict Research at Uppsala University, Sweden, and serves as director of the Uppsala University programme of International Studies and Co-Ordinator of the Southeast Asian Programme.

Carol Batchelor,Chief of Mission, UNHCR, New Delhi.

Deepti Mahajan ,The Energy and Resources Institute, New Delhi.

Dipankar Sinha,Faculty, Department of Political Science, University of Calcutta and Honorary Adjunct Fellow at the Institute of Development Studies Kolkata.

Elizabeth Ferris ,Senior Fellow, Foreign Policy and Co-Director of Brookings-Bern Project on Internal Displacement, The Brookings Institution, Washington DC.

Gladstone Xaviers,Faculty, Department of social work, Loyola College, Chennai.

Guna Raj Luitel ,News Editor, Kantipur Daily, Kathmandu.

Hari Prasad Adhikari(Bangaley) ,Bhutanese Refugee and Activist.

Heikki Patomaki , Faculty, World politics, University of Helsinki, Finland.

Research Director of NIGD, Network Institute for Global Democratisation, and Vice Director of the Centre of Excellence in Global Governance Research in Helsinki, University of Helsinki, Helsinki

Jan Breman , Social Anthropoligist and faculty, Amsterdam School for Social Science Research. He is also the Director of Centre for Asian Studies Amsterdam.

Jagat Acharya , Bhutanese Refugee and Activist, Nepal Institute of Peace, Kathmandu.

Jeevan Thiagarajah, Executive Director, The Consortium of Humanitarian Agencies (CHA), Sri Lanka.

Khassim Diagne , Senior Policy Advisor, UNHCR Geneva.

K. M. Parivelan , Information Officer UNDP/TNTRC Chennai.

Manabi Majumdar ,Fellow in Political Science, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Kolkata.

Manas Ray, Fellow in Cultural Studies, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Kolkata.

Masud Hossain, Senior Researcher, Institute of Development Studies (IDS), University of Helsinki.

Meghna Guhathakurta , Director, Research Initiatives Bangladesh.

Monirul Hussain , Faculty, Department of Political Science, Guwahati University.

Patricia Mukhim , Independent Journalist (contributor to The Telegraph, Eastern Panorama and The North East Daily). Currently Director of Indigenous Women’s Resource Centre, Shillong and also is a member of District Consumer’s Forum.

Patrick Hoenig , Currently Visiting Faculty at the Academy of Third World Studies, Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. Prior to that he worked in the UN Mission of the Congo and at UN Headquarters.

Paula Banerjee , Historian and women’s rights activist, member of the Calcutta Research Group, Faculty, Department of South and South-East Asian studies, University of Calcutta, Kolkata, India.

Pradip Phanjoubam , Editor, Imphal Free Press, Manipur.

Pradip Kumar Bose, Professor of Sociology in Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Kolkata and member of the Calcutta Research Group, Kolkata.

Prasanta Ray , Institute of Development Studies, Kolkata and member of the Calcutta Research Group, Kolkata.

Rajesh S Kharat, Department Of Civics & Politics, University of Mumbai.

Rakhee Kolita , Faculty, Department of English, Cotton College, Guwahati.

Ranabir Samaddar, Political thinker and Director, Calcutta Research Group, Kolkata, India.

Rosemary Dzuvichu , Faculty, Nagaland University.

Ruchira Ganguly Scrase, Faculty, Department of Sociology, University of Wollongong, New South Wales.

Sabyasachi Basu Ray Chaudhury , Secretary of the Calcutta Research Group and Professor, Department of Political Science, Rabindra Bharati University, Kolkata.

Samir K. Das , Political analyst on the North East and member of the Calcutta Research Group, and Professor, Department of Political Science, University of Calcutta, Kolkata, India.

Sanjoy Mukhopadhyay , Faculty, Jadavpur University and Director, Roopkala Kendro, Kolkata.

Sanjay Barbora , Regional head of Panos South Asia’s (PSA) “media and conflict” thematic concern and also the programme manager of PSA’s “peace building and media pluralism” project.

Seneka Bandara Dissanayake Mudiyanselage , Programme Manager, National Protection and Durable Solution for Internally Displaced Persons Project, Human Rights Commission of Sri Lanka.

Som Nirula , Nepal Institute of Peace, Kathmandu.

Subhas Ranjan Chakraborty , President, Calcutta Research Group and Faculty, Presidency College.

Subir Bhaumik, Eastern India Correspondent, BBC and member of the Calcutta Research Group.

Sunita Akoijam , Staff Reporter, Imphal Free Press, Manipur.

Urvashi Butalia , Dedicated women’s and civil rights activist and founder of Zubaan, Delhi, an independent non-profit publishing house. It grew out of India’s first Feminist publishing house, Kali for Women.

The Government of Finland, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), New Delhi, and the Brookings Institution, Washington DC are the sponsors of the programme. With their un-stinted support and goodwill, the programme has become one of the most well known events in the field of forced migration studies, and an academic event in Kolkata.

Preparation for the Fifth Winter Course on Forced Migration commenced on 14 December 2007, a day before the Fourth Winter Course formally ended. By that time CRG members and its collaborators had realised that the Winter Course has grown into a full-fledged programme with components of research, networking, particularly partnership between Indian and Finnish institutions, and training under innovative and different formats. This was later accepted and endorsed by the advisors during the advisory committee meeting in May 2007.

The collaborative nature of the programme was underlined from the beginning by the participatory nature of the advisory meeting. The Advisory Committee Meeting of the Fifth CRG Winter Course on Forced Migration was held in New Delhi on 11 May 2007. The participants included the following:

Ranabir Samaddar (CRG)

Paula Banerjee (CRG & Calcutta University)

Subhash Ranjan Chakraborty (CRG & Presidency College)

Sanam Roohi (CRG)

Ksenia Glebova (CRG & Winter Course alumnus)

Asha Hans (ex-Utkal University & Sansristi, Bhubabeswar)

Monirul Hussain (Gauhati University)

Partha Ghosh (Jawaharlal Nehru University)

Carol Batchelor (UNHCR, New Delhi)

Nayana Bose (UNHCR, New Delhi)

Kalpana Kannabiren (National Law School & Asmita, Hyderabad)

Khesheli Chishi Sema (Naga Mothers’ Association)

Anna-Kaisa Heikkinen (Embassy of Finland, New Delhi

Sanjay Barbora (Panos South Asia)

Priyanca Mathur Velath (Jawaharlal Nehru University)

Shiva K. Dhungana (Nepal Institute of Peace)

Gayatri Sharma (Centre for Feminist Legal Research, Delhi) Saba Hussain (Green Peace, Bangalore)

Malkit Singh (Panjab University & Winter Course alumnus)

Several suggestions emerged as a result of the advisory meeting including greater engagement with methodological issues and customizing them for forced migration studies, more emphasis on auditing and strategizing media in the course, and special focus on environmental and climate change as factors of forced migration. Induction of participants particularly from outside South Asia – it was felt – would make the course more interesting and far-reaching. The meeting also recommended the publication of a 250-300 page reader on forced migration containing select reading materials circulated for the course.

It was also acknowledged that collaboration with Finland is proving significant as more Finnish students are getting interested in joining the course. While CRG hosted one of the outstation participants for a fortnight, two of the Indian participants have been selected for making a trip to Finland. They will focus on issues of their choice relating to the status of guest workers in Finland. A delegation of CRG senior-level fellows is expected to visit the Universities of Helsinki and Tampere to attend seminars organized in collaboration with some Finnish institutions of advanced learning. Also CRG conducted some research projects on the theme of forced migration. A publication under CRG series on Policies and Practices containing the papers of Eeva Puumala, Shiv Dhungana, Priyanca Mathur Velath & Nand Kishor – all participants of the last year’s course came out and was used as reading material for this year’s course. A special issue of Refugee Watch (No. 29) – CRG’s flagship journal – was also brought out and became part of the reading material supplied to the participants. In this year, CRG has commissioned two research works on the refugees and IDPs of Nepal from amongst the participants. Three workshops on internal displacement were organized by CRG in Bangalore, Bhubaneswar and Kolkata (all in India) in 2007 in collaboration with respective state human rights commissions in India and collaborating institutions.

CRG’s winter course is a product of some of the most effective collaborations with a number of both national and international institutions. The one-and-half-day media workshop was possible with the support from Panos South Asia while two public lectures were hosted by the School of International Relations and Strategic Studies, Jadavpur University (Kolkata) and Department of Political Science,

Rabindra Bharati University (Kolkata). CRG has been successful in establishing enduring collaborations with both these universities. The field trip to Malda was organized with the help of Ganga Bhangon Pratirodh Action Nagarik Committee (Citizens’ Committee for resisting erosion of the Ganges) – an action group working with the victims of riverbank erosion in the region. Besides, the National Human Rights Commission (New Delhi) nominated one of their officers to represent them as a participant in the course.

Four areas of experiment were identified including structuring of module, distance education, participants’ profile and participants’ assignments. Suggestions were made for a short-term course with Asmita in Hyderabad and if possible, others, with university departments and research institutions. Discussions are now being conducted for finalizing such short-duration courses in other parts of the country. Also, the distance education segment can be reduced so that the time for direct orientation workshop in Kolkata can be increased. In the assignment component CRG can also think of a collaborative research of participants of two or three countries together.

Support for the winter course has also been expressed at individual level. Several faculty members came without full or any travel support and offered to contribute their knowledge and expertise for the benefit of the course. Many institutions such as the National Human Rights Commission have supported the course by sending participants. Finally, the cooperation from various quarters in circulating the announcement on the course was tremendous. In all these, the cooperation of the participants and the ex-participants was the most valuable asset. CRG remains indebted to all for making the course a success.

Due to the growing popularity of the course the advisory committee asked the organisers in 2006 to look into possibilities of organizing short courses in collaboration with willing centres and departments of Universities in India as follow-up activities. As a result of a series of follow-up activities, CRG is building partnerships with many new institutions. A number of organisations and institutions have shown willingness to collaborate with CRG on this. Besides as reported earlier CRG has collaborated with a number of institutions to organise public lectures and discussions as part of its follow-up activity. CRG remains grateful to all the organisations that have showed willingness to collaborate on programmes on forced migration.

Fellowship Programme

This year three fellowships were given to the participants of the Winter Course. Tiina Kanninen came from Tampere University and spent a week at CRG in December 2007 working on the theme, Calcutta: A migrants’ City. Two Indian participants, Sanam Roohi and Ishita De will be sent to Finland for a week and they will work on guest workers in Finland in March 2008. Again details can be found in Section 15 of the report.

Workshops Held

Prior to the Winter Course a number of workshops were held. One workshop was held in collaboration with the Other Media, Bangalore on 13-15 July 2007. The discussion in the workshop

centred on the themes of causes, linkages and responses of internal displacement, human rights laws and instruments of protection and durable solutions. Special case studies were made in the workshop on Kudremukh industrial project and Chattisgarh where armed groups are raised to counter the militants resulting in displacement of a large number of civilians.

On 27-29 July 2007 CRG organized a workshop on ‘Dominance, Development, Displacement: Rights and the Issues of Law’ in Bhubaneswar in collaboration with Sansristi. The participants were from different parts of India. Other than CRG members the resource persons included Justice D. P. Mohapatra, Chairperson, Orissa Human Rights Commission, A. B. Tripathi (retd.), former Director General of Police, Orissa and former Rapporteur of National Human Rights Commission (New Delhi), and other scholars and activists from eastern India. Imtiaz Ahmed, professor, department of International relations, Dhaka University, Bangladesh delivered a lecture on ‘Internal Displacement in Bangladesh’ in Utkal University. This was organized by CRG and the Department of Journalism and Electronic Communication and the School of Women’s Studies, Utkal University. The third workshop was held in Kolkata on 3-6 September 2007. The highlight of the workshop was the release of the report on Development-induced Displacement in West Bengal: 1947-2000 prepared by Walter Fernandes and his colleagues. Justice Shyamal Kumar Sen, Chairperson, West Bengal Human Rights Commission inaugurated the workshop. The workshop was attended by Walter Fernandes, of Indian Social Institute, Guwahati, Monirul Hussain, Professor, Gauhati University, and a group of young human rights scholars and activists from all over India, apart from CRG’s own fellows and senior researchers.

Public Lectures

Imtiaz Ahmed, Professor of International Relations, Dhaka University (Bangladesh) delivered a special lecture at Utkal University on 28 July 2007. The lecture was jointly organized by the CRG, Department of Journalism and Electronic Communication and School of Women’s Studies, Utkal University. The theme of his lecture was – ‘Internal Displacement in Bangladesh’. Besides two public lectures delivered by Heiki Patomaki and Jan Breman were organized as part of the course on 30 November and 13 December 2007. Their lectures were focused on the future of European Union and Coolie Migration in the colonial era respectively.

Research Programme

The CRG has designed and organized a number of researches on the theme of forced migration in collaboration with different institutes in South Asia. The winter course is designed to provide vital inputs to CRG’s ongoing research. CRG as a research organization takes advantage of the presence of a number of experts and specialists in the field of forced migration. Hari Adhikari and Guna Raj Luitel were commissioned to prepare two studies on the state of Bhutanese refugees and internal displacement in Nepal respectively.

The CRG has been able to set-up a well-organized network of institutions and individuals passionately committed to the cause of forced migrants in South Asia. In the field of studies and discourses on forced migration it has been able to establish itself as a premier institution.

Mohajirs: the rise…...

Defined by the Census of Pakistan, 1951, “A Mohajir is a person who has moved into Pakistan as a result of Partition or for fear of disturbances connected therewith”. Those who were lucky to survive the massacres of the partition, streamed into the Punjab and Sindh. In an unprecedented population movement, eight million people migrated to West Pakistan.

East Punjabis were allowed to settle in West Punjab. The language and culture of these refugees, these Mohajirs was identical to that of the indigenous population. The refugees settled in the urban areas as well as the rural areas. Ironically, these were the people who had suffered the terror of Partition, these were the people who best fitted the definition of “Mohajir”, yet these are the people who are seldom, if at all, are referred to as such. The government of Punjab made it easier for the refugees to settle. The people had a shared history of violence, shared culture, music, food and spoke a common language. Very quickly, they became and were accepted, in every sense of the word, as Pakistani.

The term Mohajir politically refers to those who came from the rest of India and chose to settle in Sindh. They include the first Prime Minister of Pakistan, Liaquat Ali Khan. They were the Muslim elite from the United Provinces (now Uttar Pradesh), they were the people who fought the ideological battles for the creation of a separate Muslim state in the Indian heartland. They brought with them the culture of the nawabi courts, also their language, Urdu. They came to their created ‘homeland’ with cultural linkages from the past. Assimilation with the local Sindhi population was and remains a distant after thought. Mohajirs were well educated, were already in finance and business and therefore had little problem in establishing themselves in the new country. Out of 12 industrial houses in the early years following Partition, seven belonged to Mohajirs. Observers have noted that the

transfer of populations had a profound impact on the class structure of west Pakistan as with the exception of some migrants from East Punjab those from other parts of India were predominantly urban and literate. They included the traders, primarily from Gujarat and Bombay, who subsequently constituted the industrial class of Pakistan for two decades.

Politically, the leadership of Pakistan was Mohajir dominated. Urdu became the state language of Pakistan, giving Mohajirs a definite edge for jobs in the public and private sectors. There was no reason for the Mohajirs to give up a lifestyle, culture and a language that they had transported across the border. The Mohajir elite dominated the bureaucracy, business and politics till the coup of Ayub Khan in 1958. Better qualified, better educated and well trained they were cream of business and the civil services. Ideologically, they differed from the indigenous population of Pakistan. The movement for Pakistan though initially founded by nawabs and landlords was quickly taken over by the urban professional classes who organised the Muslim League on democratic lines. Consequently, as Burke has noted in The Continuing Search for Nationhood (1991), following the creation of Pakistan the refugees who had come from the cities of north and central India began to work for some of form of a representative political system. There were other differences too – Mohajirs were secular and desired to have a clear separation between religion and the state, now that the Muslim state had been created. Economically, though Pakistan was largely an agricultural economy, refugees who had come from urban areas had little interest in using public funds in agriculture.

………. And Fall

With the death of Jinnah and the assassination of Liaquat Ali Khan soon after the creation of Pakistan, politics became chaotic. With Ayub Khan and his policies began the decline of Mohajir elite power. At the cost of Mohajirs, other refugees, particularly those in Punjab were resettled. His Basic Democracy scheme, which was a system of local government, encouraged the free flow of people within West Pakistan. Pathans gained hugely as they now moved south, to Karachi for employment. The transport industry in Karachi was and remains completely Pathan dominated. Civil servants were sacked, coincidentally almost all of whom were Mohajir. The Punjabi presence began to increase in the bureaucracy, at the cost of Mohajirs. Finally, the transfer of the capital of the country from Karachi, which was the Mohajir stronghold to a site near Rawalpindi (later to be known as Islamabad) further undermined Mohajir importance and power. But it was left to Zulfiquar Ali Bhutto, the “son of Sindh” to hammer the nails into the coffin. In the early 70’s the Language Bill of Sindh gave Sindhi the same importance as Urdu and the restructuring of the Quota System introduced the controversial rural vs. urban division only for the province of Sindh effectively allowing Mohajirs to compete for just 7.6% of all nationalised jobs. These two measures acted as external catalysts to the process of a renewed political identity formation for the Mohajirs. Bhutto’s nationalisation of industry and finance had a devastating affect on the Mohajir community. There was a huge purge of the bureaucracy, again a large majority of those sacked were Mohajir. General Zia’s time was controversial. Some say that the military turned a blind eye to the rise of the Mohajir Quami Movement (MQM) at a time when most political activity was frowned upon. But in the established power structures such as the civil bureaucracy the share of the Mohajirs further shrank. Military rule meant increased Punjabi domination of the army. The Mohajirs withdrew, as it were, to urban Sindh for the defence of what they saw as their core interests.

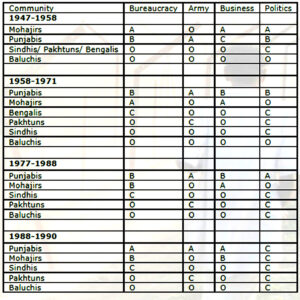

The following table by Dr. Mohammad Waseem charts the decline of Mohajir power in post independence Pakistan. Published on May 8, 1990 in Dawn it gives a fairly accurate summary of the arguments presented above.

Relative Change in Community Influence: 1947-1990

(Community power ranked on a scale of A, B, C, O from highest to lowest, respectively.)

Mohajirs have never had a presence in the armed forces of Pakistan. Their power in the bureaucracy is now a far second to that of the Punjabis. In business, once an undisputed Mohajir stronghold, they have been relegated behind Punjabis. Without doubt, Mohajirs have been subject to systematic discrimination. Yet, while all this is relevant to this discussion on the decline of a community that had pioneered Pakistan, these do not explain the rise of the Muttahida Quami Movement (MQM), a party which represents most lower and middle class Mohajirs.

Politically, the Mohajir community is represented for better or for worse, by Altaf Hussain and the MQM. Though the MQM is hardly supported by the elite among Mohajirs, it remains the only access to power for the majority of Mohajirs, the change in name (from Mohajir to Muttahida) notwithstanding. To its credit, the MQM has steered clear of religious fundamentalism and has remained a strong supporter of women’s rights. The organisation prides itself on its working class origins. Altaf Hussain remains an idealist who began fighting for the recognition of the Mohajirs as a legitimate fifth nationality within Pakistan with due rights and representation and who now vows to dismantle the oppressive feudal system thereby uplifting the masses of Pakistan, riding on a middle-class support base.

Mass mobilisation: The Mohajir Quami Movement

In the elections of 1993, once again the MQM won 27 seats in the provincial assembly, reaffirming its stature as the third largest party in Pakistan after the Pakistan’s People’s Party (PPP) and the Muslim League (ML). The Mohajir Quami Movement, which sprang into life in 1984, had started as an entirely middle/working class movement, with very little to do with the elite. Most of its funding came from the working classes, though large Mohajir business houses are known to have been persuaded into making generous “voluntary” donations. The MQM is, in some ways a unique phenomena: class based, urban, young, well knit and able to mobilise very quickly. Its network in Karachi is vast and well entrenched. The MQM is more than just a political party. Observers have noted its influence in connected organizations, such as labour unions, student organization, women’s organization and welfare organizations. Verkaaik has noted that most MQM workers and members live in MQM areas that facilitate access to services the state does not or cannot supply such as primary schools and financial support for widows. The MQM also has the largest percentage of educated membership among the national parties of Pakistan barring the Jamaat-i-Islami, which is not surprising considering that the Mohajirs are among the most highly educated peoples in Pakistan.

Myths surround the origins of the MQM. Its sudden appearance on Karachi politics has left commentators guessing. Created in 1984, it captured 46.5% of the seats in the Karachi Municipal Corporation, in the local elections of 1987. Some subscribe to the theory that Zia deliberately propped up the MQM to counter the PPP led Movement for Restoration of Democracy (MRD) in rural Sindh. Allegations that the MQM was started and funded and encouraged by the military and ISI while other political movements were brutally suppressed abound. Expectedly, Tariq Meer, the joint chief organizer of the MQM (UK & Europe) dismissed these allegations in an interview with the author, “Ridiculous. If the military or anybody could create a party, things would be very different…How can Zia make Altaf Hussain a public leader?” He further said in response to a question that it had been repeatedly said in accusation that India was sponsoring the MQM, “anybody who talks about democracy in Pakistan is labelled an agent of India”.

The origins of the MQM lie in its roots. Mohajirs have myths. There is the myth of a common identity based on a perceived sense of systematic discrimination; the myth that they are the creators of Pakistan and are therefore more Pakistani than the Sindhis and others. There is also the myth that all those who crossed the borders in 1947 suffered great personal loss and sacrifice for the new country. A common identity had been forged with a common language. Urdu had forged a common link and Urdu was the passport to the civil services, and financial power. It has also been argued that the Muslim League had its intellectual growth in the dusty towns of Uttar Pradesh, Aligarh, Meerut, and others. Also that the Mohajirs had made great personal sacrifices to come to Pakistan, though this holds true probably more for those who had migrated to Punjab. It was a much more peaceful transition for those who came to Sindh. But myths forge an identity. The Mohajirs have created theirs, overcoming linguistic and cultural differences.

The politicisation of Mohajirs

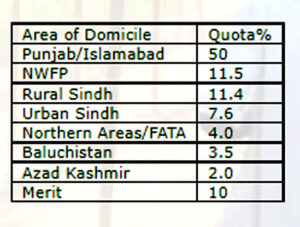

The Zulfiquar Ali Bhutto era was central to the intellectual foundations of Mohajir nationalism as during his time administrative procedures that compartmentalised Sindh and Pakistan society were established, and regional cultures such as that of the Sindhis were promoted. The Language Bill, the Quota System and the nationalization of industry and financial institutions played an important role in politicising the Mohajir identity. Bhutto came to power in 1971 at a particularly challenging point in Pakistan’s history. The Eastern half of the country seceded to form Bangladesh. Till 1971, power sharing in Pakistan primarily referred to that between the Eastern and Western wings. The Quota System was first introduced in the 1950’s in deference to Bengali demands. The Bhutto period had to contend with power-sharing with the provinces that remained in Pakistan: Punjab, Baluchistan, the NWFP and Sindh. Conflicting demands in West Pakistan earlier suppressed, now found a voice. The Quota System of 1973, much reviled by Mohajirs, was a response to changing political reality. Based on population ratios, the designated quota for federal government employment is as follows:

The quota system in public sector employment

Source: Government of Pakistan, Establishment Division, memo no. F8/9/72 (TRV) 31 August, 1973. Islamabad

The Mohajirs took exception to the rural-urban divide exclusively for Sindh. It institutionalized the marginalization of Mohajirs. Bhutto played to the gallery, appeasing his constituency, that of rural Sindh. Tariq Meer speaks not only for Mohajirs, but for any thinking person on this issue: “If the quota system was such a wonderful thing for the rural population of Pakistan, then it should have been introduced everywhere. Why has it been only in Sindh? Don’t other people in Pakistan have the same problems vis-a-vis urban vs. rural? The rural populations of Punjab, Baluchistan and NWFP are as illiterate, as backward and as oppressed as in Sindh.” Second, its been argued that the populations of Karachi, Hyderabad and Sukkur were underestimated at the time, so as to reduce the quota percentage. This system was intended to be in place for 10 years, but successive governments have voted for its continuity: the most recent vote to extend this by a two-third majority was held in July 1999. Opposed only by the MQM in the National Assembly, the Quota System is now in place till 2013.

The Language Bill introduced in 1972, elevated Sindhi to the status of official language for the province, equating it with Urdu. Considering how important Urdu is for the Mohajir population culturally in addition to linguistically, it was not surprising that the introduction of this Bill created large-scale rioting. It was Bhutto’s populist nationalisation of large-scale manufacturing industry and financial institutions which not only brought the growth rate down to 3%, the lowest in Pakistan’s history, but more importantly, immensely raised the level of Mohajir political awareness. Privately owned commercial banks and insurance companies were brought under government control. Since most of these were Mohajir owned, the result was debilitating. Overnight, fifty percent of the workers were now Punjabi – the Mohajirs who formerly dominated these institutions could now form just 7.6% of the work-force.The overall effect of nationalization filtered down from the elite to the working classes, and this where the mass base for a disfranchised, educated but unemployed community began to take shape. Even private educational institutions were nationalized, thus reducing access for Mohajirs to a system of networking and patronage.

In addition to Bhutto’s policies, external factors such as the Gulf boom of the late 1970s added fuel to the fire. Pakistanis flocked to the Middle East for employment – a large number of these were Mohajirs. Remittances from there to their middle-class/lower middle class families created new socio-economic groups. Afghan war refugees, who numbered close to 3.5 million, settled largely in the NWFP and Baluchistan, but had a staggering effect on the ethnic mix of Karachi. It encouraged further Pathan migration down south. It was in such an atmosphere that the All Pakistan Mohajir Students Organisation (APMSO) was formed in the campus of Karachi University, in 1978. Altaf Hussain gave this powerful emotion a concrete political identity.

The Zia years undid some of the nationalization of industry but these were seldom returned to their original Mohajir owners. And the bureaucracy, a critical ally for Zia, stood to gain. During Zia’s time, the military-bureaucracy network dominated civil society in Pakistan. A large number of civil and military bureaucrats, mostly Pathans or Panjabis, amassed personal fortunes through the spoils of the Afghan war. Needless to emphasize, the Mohajir community, elite or working class, stood nowhere in the line of beneficiaries. The MQM focussed equally on economic and political issues. Its slogans on access to employment attracted the working classes. Its accent on economic factors drawing on its obvious ethnic appeal galvanized the movement. It took Karachi by storm. Soon the MQM was seen as a highly powerful and effective political force, led by Altaf Hussain who demanded that the Mohajirs should be recognized as the fifth nationality of Pakistan and that they should be allotted a 20 percent quota at the Centre and between 50 percent and 60 percent in Sindh. Tensions between Pathans and Mohajirs increased partly due to a constant struggle for scarce resources and for control of Karachi. The first large-scale riot between the two ethnic groups took place in 1986. This in turn consolidated the need for the Mohajirs to have a political party to represent their interests: the MQM grew in defiance of oppression. The party swept the Local Bodies elections of 1987 in Karachi and Hyderabad.

The growth of the MQM as the Mohajir Quami Movement can be divided into three phases. The early phase (1984-1988) saw the rapid rise of the party to political hegemony. The middle phase (1988-1990) saw a short-lived coalition with the PPP in Sindh followed by violent partying of ways. Short of an absolute majority the PPP entered into an agreement with the MQM, which lasted one year. Ire against Sindhis grew, Pathan disenchantment temporarily fell to the side-lines. The MQM established its presence in the other urban centres: Hyderabad and Sukkur. This was not without cost. For example, about 250 Mohajirs were killed in a Hyderabad bomb blast in Sept 1988 allegedly by the Jiye Sindh Progressive Party, a pro-Sindhi organisation. The final phase (1990-1995) saw the MQM enter into an alliance with Nawaz Sharif and the Pakistan Muslim League both at the Federal level and in Sindh, as it emerged again as the third largest political force in Pakistan in the 1990 elections. This phase saw the beginnings of a shift in ideology: the MQM moved away from its ethnic platform to a more economic, class-based platform. In the early 1990’s a small faction broke away, known as the Haqiqi faction which claimed to believe in the original ideology of the MQM. The MQM was now split into the MQM (A), the Altaf faction, and the MQM(H). Many commentators confirm, including the Amnesty International that successive federal governments and the military in order to weaken the MQM (A) supported the MQM (H). Violent clashes, now between the MQM (A) and MQM (H), in addition to earlier ethnic tensions continued. On the 19 June 1992, the army was called in to quell the chronic violence in Karachi, which was fast becoming another Beirut. It was also during this phase that Altaf Hussain, fled Pakistan in fear of his life. He left Karachi in 1992, for London and has not returned since.

Evolution of the MQM: Now, Muttahida (1997 -)

The MQM (A) officially changed to Muttahida Quami Movement, in July 1997. Ideologically, the shift to its homegrown philosophy of ‘Realism and Pragmatism” had begun in the early 1990s. In its words as conveyed in its web-site (mqm.org), the MQM is working toward establishing a pragmatic social and political order that provides sanctity of life and property for people of all social strata. It provides ample opportunities to the members of the disadvantaged class to better their lives without taking anything away from the advantaged class. Further, the MQM believes in creating an economic system that makes all national resources available to all citizens of Pakistan, purely on the basis of merit and hard work, without any regard to race, religion, gender, language or other basis of discrimination.

The vision of the MQM has thus broadened from a primarily ethnic focus to a social reform agenda. There are however, no clear cut policies, no set goals except an overall change of the prevailing system and greater economic benefits to all the lower/working classes. Unlike before, there is no defined constituency for MQM workers to target, unless, of course, the target is the entire middle class. Physically Karachi and Sindh remain synonymous with the MQM. However the willingness of the MQM to form coalitions with those they decry rhetorically shows that access to power is a central concern for the MQM. The Muttahida Quami Movement (MQM) is here to stay. In the 1997 elections it emerged as an important power broker once again, as the third largest political force in the country. Its agenda has moved much beyond Karachi, Sindh and ethnic politics: it now talks of transforming feudal culture, of an equal distribution of resources, of the improvement of the conditions of the downtrodden masses of Pakistan, who according to rhetoric are 98% of the population. Its immediate target is the rising middle class of Pakistan, and if it is to succeed in its ambitions, it must tap this resource. However given its record of violence and its now remote control through long distance leadership, the MQM may be unequal to the task.

The challenge of the MQM now lies in delivering its message of social reform to a less recipient target group, many of whom still equate Muttahida with Mohajir. For the Mohajir community the past five decades have seen a shift in the balance of power. The first ten years after independence, elite Mohajirs ruled Pakistan. Forty years later, elite interests have given way to a mass-based grassroots movements, struggling to make a real impact in a country where any democratic political activity has become increasingly difficult. How much of an impact will they have on governance, how much of a representation will they have in the real corridors of power, and when will these “chosen” refugees be completely accepted and represented in all strata of society remains unclear.